TRANSLATION ATTEMPTS

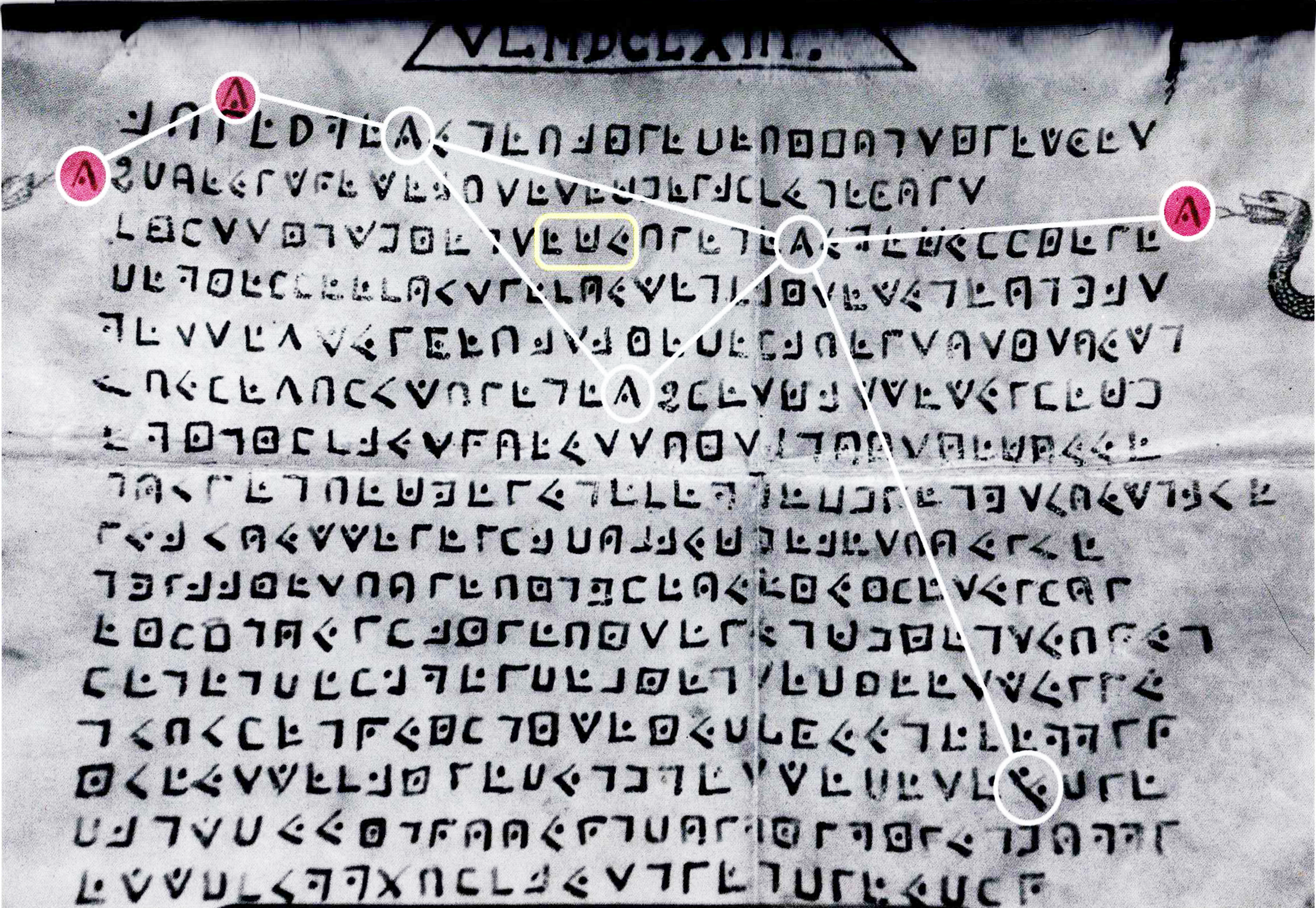

Since the publication of the enigmatic cryptogram in 1934, countless treasure hunters, amateur cryptologists and adventurers have attempted to decipher it – mostly with little success. Although the underlying code – a variant of the Masonic script – has largely been deciphered, the resulting text appears confused, full of linguistic errors and without a clear message. No wonder that theories ranging from constellations and Herculean tasks to occult recipes from the Middle Ages are circulating. The British researcher Nigel Ward was one of the first to systematically point out possible errors in the code – but it is only through the “error logic” presented here that the puzzle can really be made tangible. This approach assumes that many supposedly incomprehensible passages are the result of simple, comprehensible writing and reading errors – and that the original writer was neither a native speaker nor skilled in grammar. The results: surprisingly clear, historically plausible – and a possible key to the true meaning of the cryptogram.

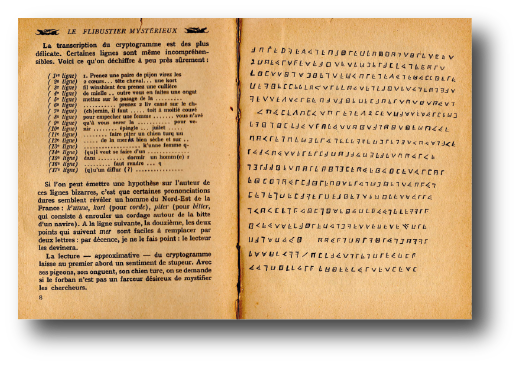

Transcription by Nigel Ward (excerpt)

Since the publication of the cryptogram in 1934, various people, especially hopeful treasure hunters, have tried to make sense of the text of the cryptogram. The crux of the matter: The code itself is unambiguous, the “character substitution” (replacing characters of the code with letters) largely undisputed. But the resulting “plain text” is anything but clear. This opens the door to wild speculation about the “intended” content. This can be read in Günter Seuren ‘s book “Treasures of the Earth” from 1989:

“After much thought, Wilkins believed he had found a link to Greek mythology: […] Gradually, Wilkins discovered that le Vasseur had linked the coded signpost to his treasure with yet another adventure in Greek mythology: just as Hercules had to perform twelve arduous labors, Wilkins had twelve tasks to solve in order to find the hiding place.”

The constellation Ecu de Sobieski near Mezino

Emmanuel Mezino reads the cryptogram as a star chart, but he uses an obvious forgery of the document as the basis for this, although he claimed for a long time that it was the only original. He discovers the word ECU between three A-signs (on line 3) and interprets them as the constellation Ecu de Sobieski. However, he has to invent non-existent signs into the cryptogram in order to make sense of the constellation and give his own theory a minimum of weight. The question arises as to what good it would do a pirate to depict a star constellation in a cryptogram, especially as Mezino refers to a part of the cryptogram when locating the treasure, which is obviously forged or copied from Edgar Alan Poe’s “Gold Bug”.

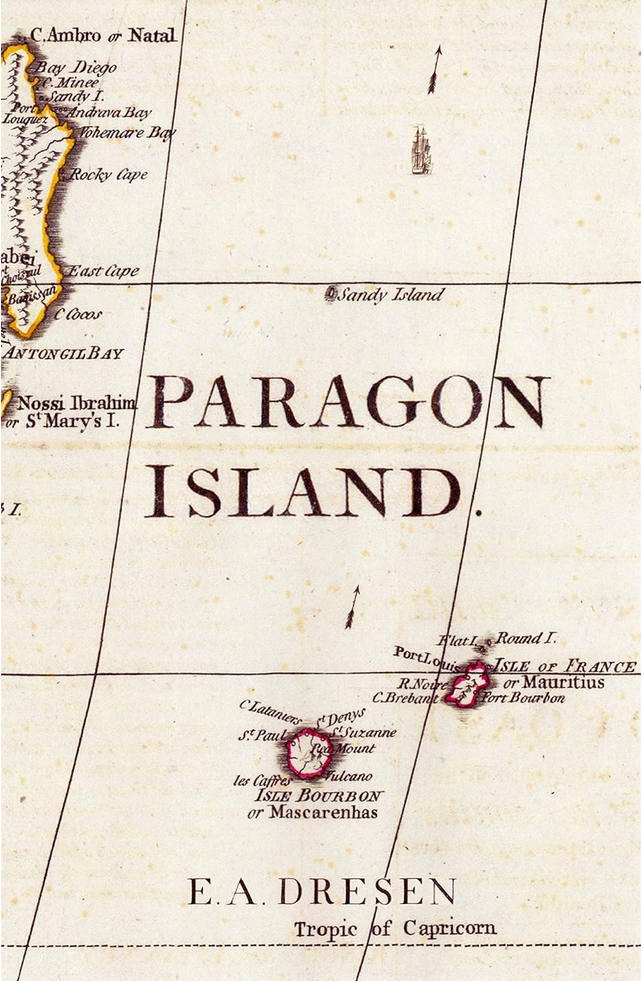

E. A. Dresen mixes fact and fiction at will in his novel “Paragon Island”. In addition to very exciting approaches (especially in relation to the “special characters” in the cryptogram), his imagination runs wild, especially when it comes to the “translation” of the cryptogram text. Unfortunately, it is pure fantasy that is subordinate to the dramaturgy of the novel.

All these approaches to the content of the cryptogram have one thing in common: none of the authors can justify their interpretation even remotely cryptologically, graphologically, systematically or logically. Everything remains pure speculation.

Cyrille Lougnon, an otherwise outstanding researcher, takes it to the extreme by claiming that this “impenetrable text” makes absolutely no sense and writes:

“But strangely enough, every day there are new followers of his enigmatic message who, unimpressed by his obvious hermeticism, make an effort to find one.”

This diagnosis makes it easier for him to indulge in his fantasies that the cryptogram points to a specific place on La Réunion where the treasure is buried. Unfortunately, the historian fails to ask whether it is at all plausible and probable that the imprisoned pirate was able to hide this document somewhere and conceal it unnoticed under the only item of clothing, a long shirt, which he wore on the way to the gallows, in order to throw it into the audience afterwards. Like most hopeful explorers and treasure hunters, Lougnon was taken in by de La Roncière’s legend.

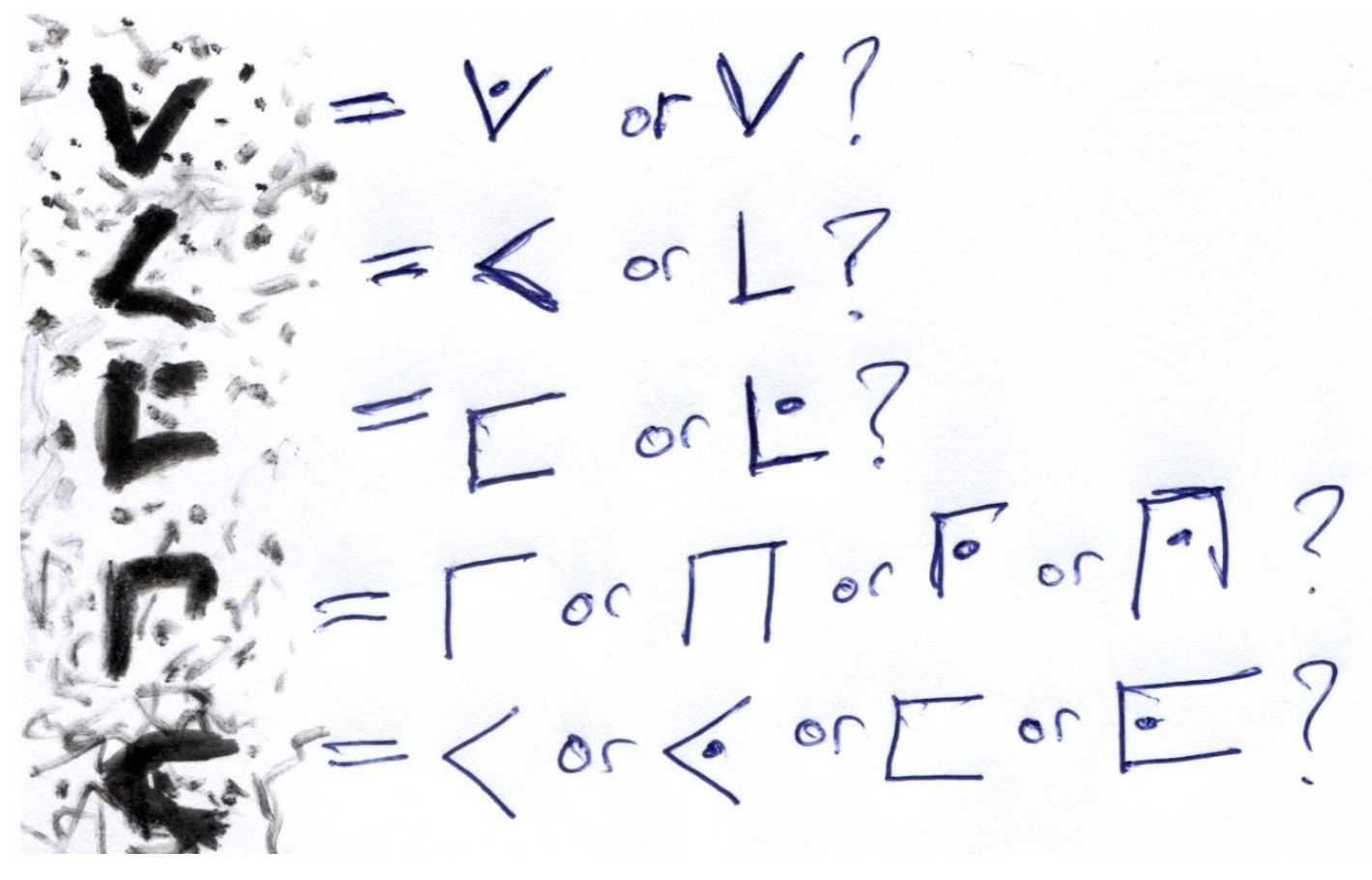

Approaches to a “logic of error” with Nigel Ward

In fact, there are also serious and systematic attempts to make sense of the cryptogram. Nigel Ward shows on his website that the Pigpen cipher, i.e. the Freemason code, contains a number of ways of misspelling characters or misinterpreting written characters. (De La Roncière had already pointed this out in his book: “Another disadvantage is that the pirate has not always marked the first letter of the group with a dot, so that you can read t where it should actually be s, f where it should actually be e, etc.”) In the end, however, Ward also falls into the temptation to interpret in order to give the content a recognizable meaning, instead of consistently adhering to his system.

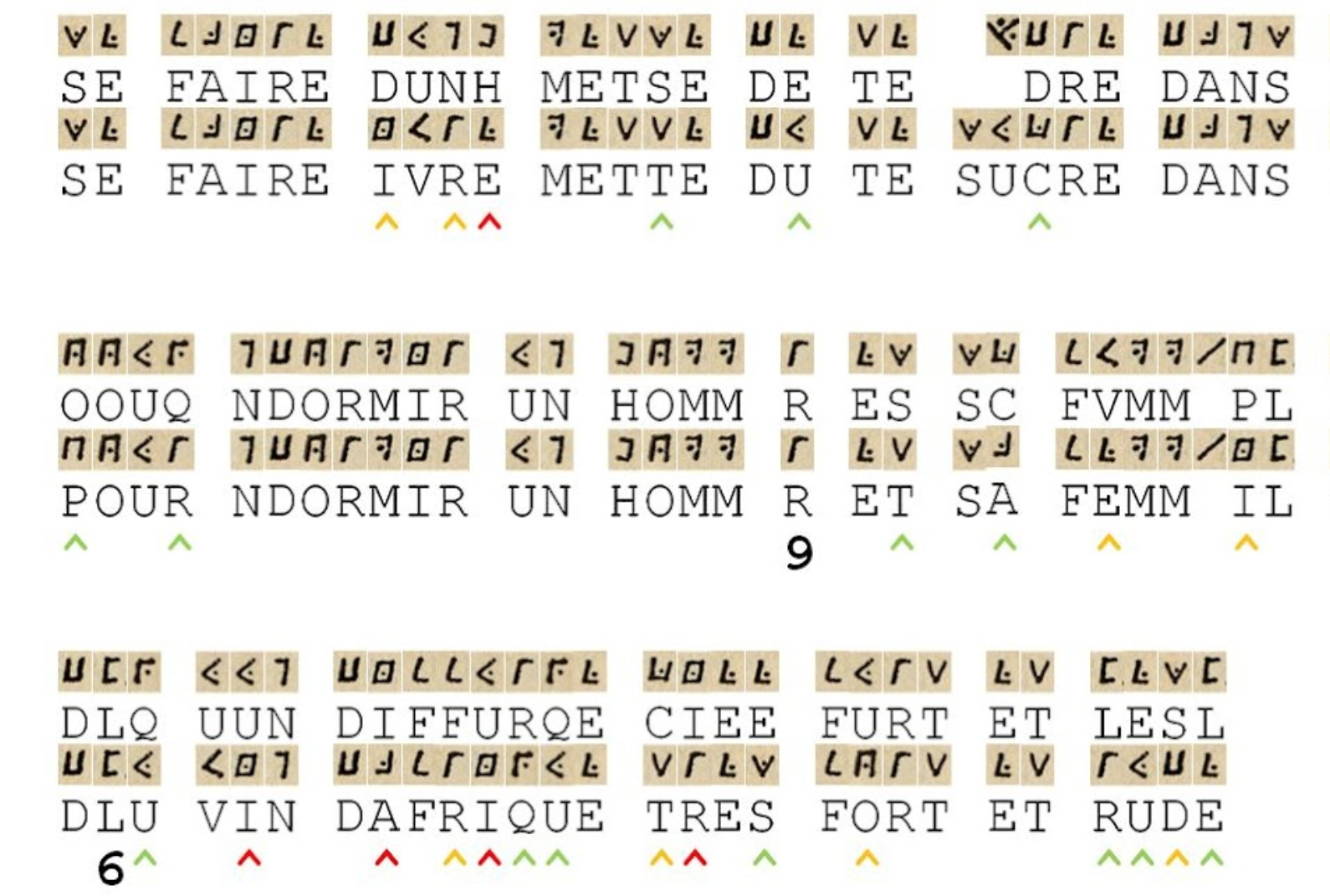

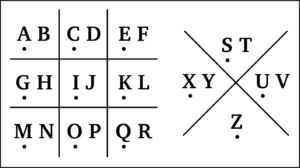

In purely mathematical terms, there are not that many options. If you analyze the characters carefully, you can identify a clearly definable “error logic”, i.e. clearly identifiable potential sources of error. Let’s take a look at the Masonic code used in the cryptogram:

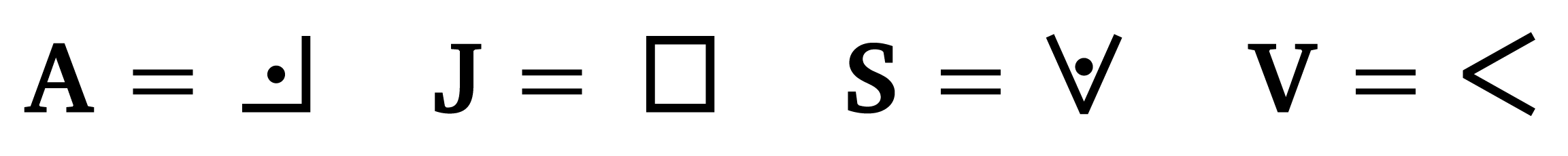

The code works according to the substitution principle, i.e. one character replaces one letter. To encode a letter, you take the strokes that “frame” this letter. If it is the first letter in a field, a dot is placed in the middle of the character in addition to the frame.

Examples:

We can distinguish between right-angled characters (first grid, letters A to R) and acute-angled characters (letters S to Z).

The error options result from dots that have been forgotten or placed too much, from missing or accidentally placed dashes, from misinterpretation of dots as dashes or of dashes as dots and from “wrong” angles, whereby right-angled characters become acute-angled or vice versa.

Decryption has shown that there can also be (a few) errors over two steps. This confirms the theory that there were very probably two scribes: An author of the original text and a copyist who used this original text to create the cryptogram as we know it.

In addition to errors due to incorrect use of the code or transcription, the text is full of grammatical and lexical errors. This means that we can assume that the author of the original text was not a native French speaker and had no theoretical language training. As a result, the scribe wrote phonologically, i.e. he wrote the way he spoke, and he sometimes mixed up similar-sounding words. If we take the historical and geographical context into account, we can assume that the author of the original text did not come from France, but most probably belonged to another ethnic group. Knowing the colonial situation in the Indian Ocean in the 18th century, it is reasonable to assume that this was an African slave, presumably better off, who had been in the service of his master for some time and at least spoke French. There is no evidence of Creole influences in the language. This means that the text must have been written before the development of these independent dialects or language variants.

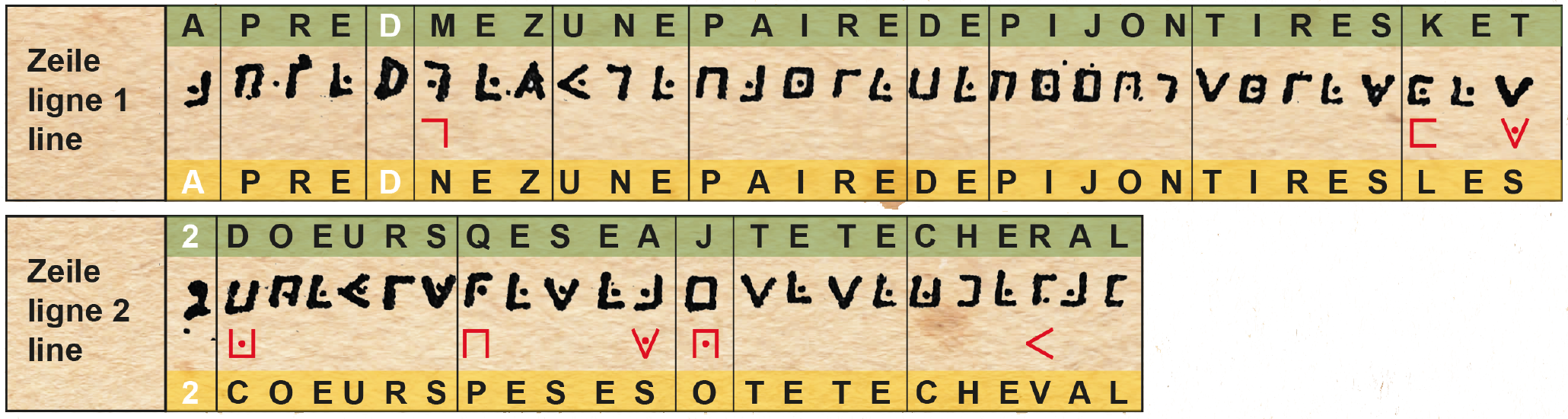

Transcription example

The pigeons

Original transcription:

APREDMEZUNEPAIREDEPIJONTIRESKET

2DOEURSQESEAJTETECHERAL

Cleanup:

PRENEZ UNE PAIRE DE PIJON

TIRES LES COEURS PESES O TETE CHEVAL

Modern inscription:

Prenez une paire de pigeons. Tirez les coeurs, pressez[-les] à la tête du cheval.

Translation:

Take a pair of pigeons. Pull out the hearts and press them against the horse’s head.

Linguistic notes:

The writer uses -es twice instead of -ez (command form), which is phonologically identical. He is probably confusing the two similar verbs peser and presser (= to press).

Estimated reliability of the transcription: 85%

Comment:

The recipe for halving pigeons alive has been used by a number of authors since the 16th century at the latest

. Girolamo Ruscelli listed it as a remedy against the plague as early as 1557 in his 6-volume work “De secreti del reverendo donno Alessio Piemontese”. There is no evidence that it was also used to treat horses. In later sources, the recipe is mainly recommended against mental illnesses such as melancholy

.

The complete new transcription with interpretations and historical sources can be found in the article “DIE NEUE TRANSKRIPTION” (only for PREMIUM members).

Sources mentioned:

– Seuren, Günter: Treasures of this earth. Adventure, luck and gold. Munich: Schneekluth Verlag, 1989.

– Mezino, Emmanuel. Mon trésor à qui saura le prendre. 2014.

– Dresen, Erik Alexander: The Paragon Island. Augsburg: Erik Alexander Dresen, 2015.

– Lougnon, Cyrille: Olivier Levasseur dit “La Buse” – Piraterie et contrebande sur la Route des Indes au XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Riveneuve, 2023.

– Ward, Nigel: The Cryptogram of La Buse. Available online at: https://sites.google.com/view/labuse.

All articles Cryptogram

The cipher that has been sprouting the fantasies of many people in all its aspects for 90 years.

All articles La Buse

The life and work of the most famous French pirate of the 18th century.

All articles Backgrounds

Stories and history about the “Golden Era of Piracy”, La Buse and the cryptogram.