THE END OF A LEGEND

The legend surrounding the cryptogram and the treasure of the pirate Olivier Levasseur has persisted for decades – fueled by romantic notions, popular myths and ever new attempts at interpretation. But a sober analysis of the historical, linguistic and cryptological facts paints a clear picture: the document was not written by La Buse. Several independent findings – from the script used to the alphabet to the correspondence with a map from the time after his death – clearly speak against the authenticity of the story. The cryptogram thus loses its status as a pirate’s treasure map and turns out to be a later construct. What remains is a fascinating mystery – but one with no real connection to Olivier Levasseur or a lost treasure.

The treasure map in Stevenson’s “Treasure Island” (1882)

The myth of La Buse and the cryptogram persists. It’s time to dispel it – even if it hurts a little. There are at least six reasons that speak against the story. Each one would be a strong argument in itself.

From what we know, the likelihood of pirates burying anything of value anywhere is vanishingly small. Even treasure maps, as we know them from popular culture, do not exist – at least not yet. The image we have of them comes largely from Robert Louis Stevenson’s “Treasure Island”. No X has ever marked the location of a treasure on a map. And yet there is a certain longing in many people that it might be true. In fact, there are people who claim to have seen treasure – or know someone who knows someone …

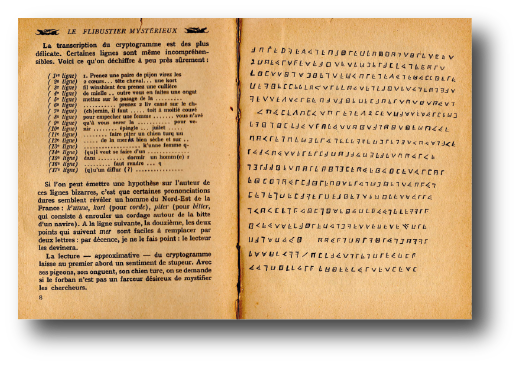

The story of the pirate who threw a note into the audience shortly before his execution (see “Le flibustier mystérieux”) has fascinated all those who want to believe it for 90 years (and I was one of them until recently). Who wouldn’t want to be the one to open a chest overflowing with gold, silver and precious stones by the light of a torch?

1. the Masonic script

We have shown that the probability that Olivier Levasseur knew the code is negligible. Freemasonry only reached the Indian Ocean towards the end of the 18th century: the first lodge on La Réunion was founded in 1775, the first on Mauritius in 1778.

Of course, the founding of a lodge does not necessarily prove that Freemasons were not already present – but the period in question (1721-1730) was a time when the movement was just beginning to spread in Europe. The Masonic script was still being developed – from the nine-letter grid to the form we know today. And it was certainly not pirates who drove this development forward.

2. the situation as a prisoner in the dungeon

The idea that Olivier Levasseur wrote the cryptogram as a prisoner in a dungeon is quite absurd. Who would have brought him paper, ink and pen? And where would he have hidden the document – on the way to the gallows?

Some authors claim that he wore it around his neck. This is absolutely out of the question – his guards would certainly have taken it from him. Cyrille Lougnon is of the opinion that La Buse wrote the cryptogram shortly after the attack – which is at least more likely. But even then, the question remains: how could he have concealed it from his jailers?

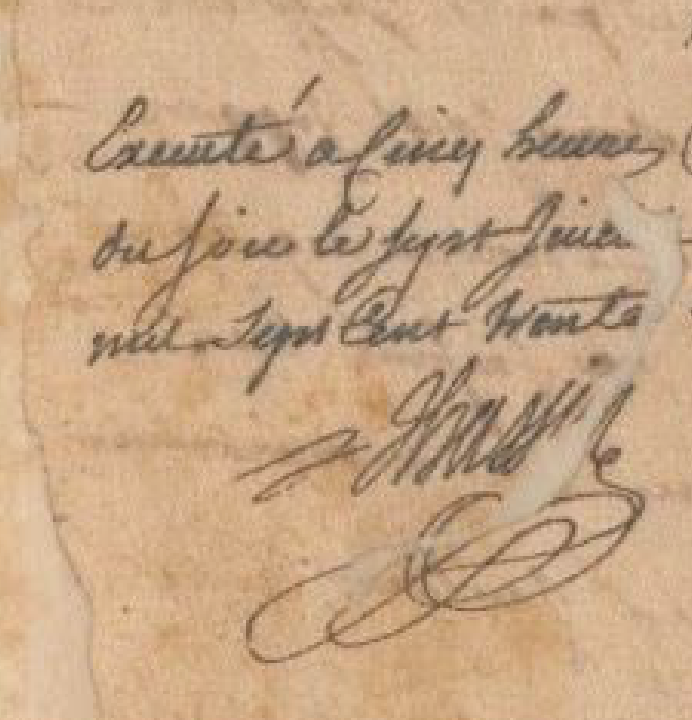

Executé a Cinq heures du soir le Sept Juillet mil Sept Cent Trente

The main argument remains: There is not a single contemporary witness account of the famous scene with the note. Such an incident would certainly have caused a considerable uproar. The laconic note next to the death sentence simply reads: “Executed at 5 o’clock in the evening on the seventh of July 1730.”

3. the alphabet

The cryptogram clearly contains the letters J and V. As has been proven, these letters were not part of the French alphabet in the period 1721-1730. The model for the code appeared in 1745 in the book L’ordre de francs-maçons – 15 years after the death of the pirate. The letters J and V are missing from it.

4. the language

Analysis of the New Transcription of the cryptogram clearly indicates that the scribe was not a native French speaker. The text is written phonologically (“as one speaks”), contains grammatical errors (fume instead of fumez) and shows lexical-semantic weaknesses (orefils instead of orifice, peser instead of presser).

Such errors are what you would expect from a non-native speaker. It is practically impossible that a French speaker would have deliberately imitated these errors – and why should they? There would have been far more plausible means of making the code more difficult. Instead, the text was created in two stages: a non-native speaker wrote the original text, which was later used by a “planner” as filler text for the space between the “special signe”. This is how the intended gibberish was created, which treasure hunters and researchers have been trying to understand for decades. (All details in the article “THE NEW TRANSCRIPTION”).

5. the map

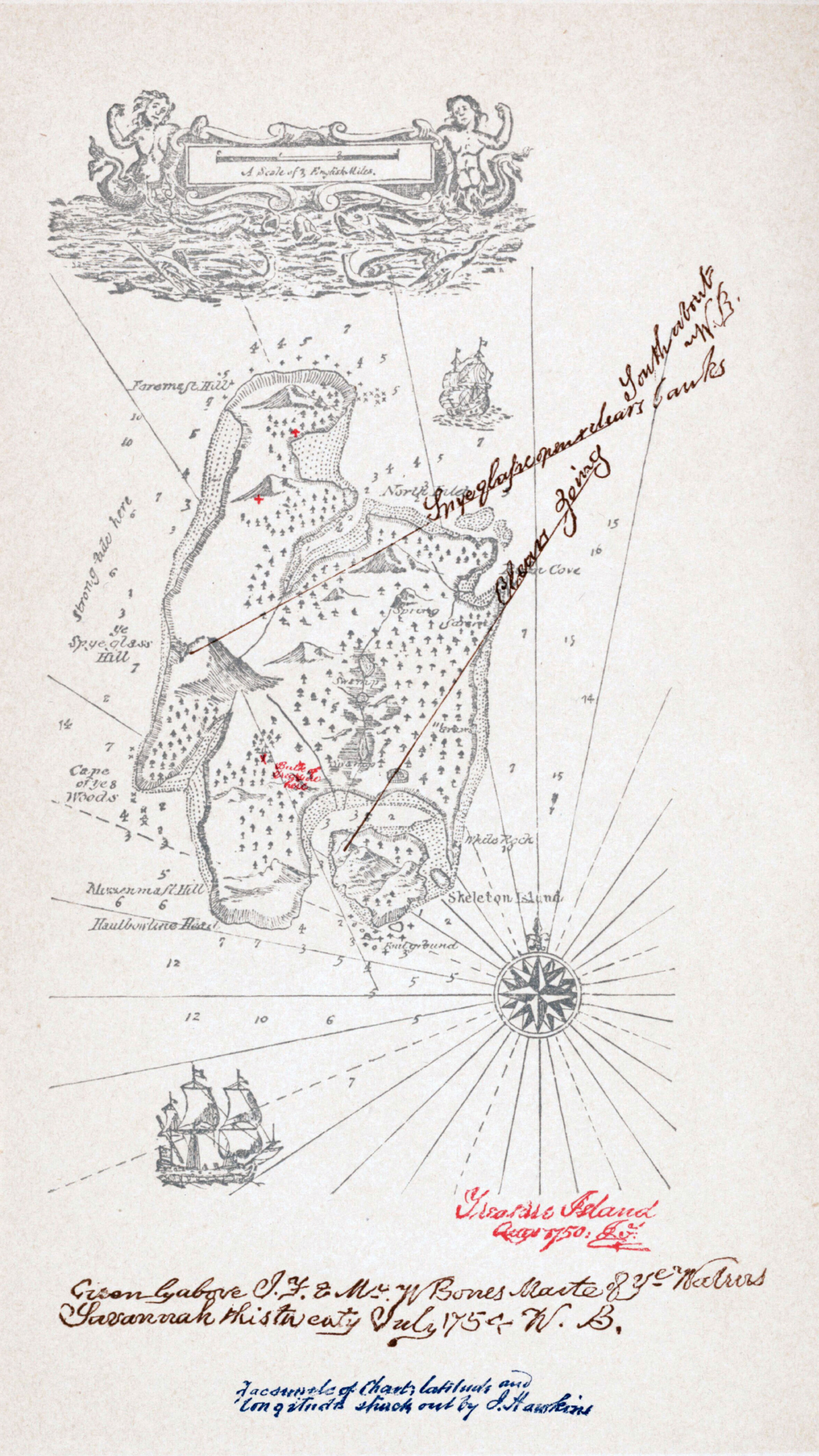

Probably the most convincing argument is the correspondence of the “special signs” in the cryptogram with a map from 1753. If the cryptogram is placed on the map at the correct magnification and rotated 45° clockwise, four geographical markers match exactly: Port Louis, Piton de la Découverte, Piton de la Petite Rivière Noire and the southern point of the island. A mere coincidence is therefore out of the question. The map was not published until 23 years after the violent death of Olivier Levasseur.

6. the complexity

If you want to hide a treasure and find it again later, you need to think about two things: How do I mark the location as inconspicuously as possible in the terrain and how do I remember the location with the markings? What we have here is a highly complex system of coded text with hidden symbols that correspond to geographical points on a map. And that’s not the end of the story. Up to this point, there is still no indication of a specific location on the map. The system must therefore still have a continuation (see “The map”). The effort involved bears no relation to the desired purpose! It is absolutely implausible why a pirate would have chosen this route if there were clearly much simpler ways of memorizing and marking a location.

Conclusion

The verdict is clear: Olivier Levasseur was not the author of the cryptogram. Charles de La Roncière’s assertion is false. (Side note: The “hard Ks” he uses to justify La Buse all turn out to be Ls – KET = LES, KORTFILT = L’OREFILS, KE = LE, IUDFKU = RECELE).

The story turns out to be what it always was: a legend that refers to a historical event (the death of La Buse) but has no relation to reality in terms of the cryptogram.

And there is another important consequence of this: If the cryptogram is not from La Buse, it almost certainly has nothing to do with an alleged treasure. All treasure hunters who rely on the cryptogram need to fundamentally rethink their theory.

Sources mentioned:

– Stevenson, Robert Louis: Treasure Island. London: Cassell & Company, 1883.

– Académie française: Dictionnaire de l’Académie françoise. 4e édition. Paris: Bernard Brunet, 1762.

– Pérau, Gabriel-Louis Calabre: L’Ordre des francs-maçons trahi et le secret des Mopses révélé. Amsterdam: Jean Neaulme, 1745.

– Lacaille, Nicolas-Louis de: Plan de l’Isle de France tracé sur les observations géométriques et astronomiques faites en 1753.

– Lougnon, Cyrille: Olivier Levasseur dit “La Buse” – Piraterie et contrebande sur la Route des Indes au XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Riveneuve, 2023.

– Dresen, Erik Alexander: The Paragon Island. Augsburg: Erik Alexander Dresen, 2015.

– de La Roncière, Charles de: Le flibustier mystérieux: histoire d’un trésor caché. Paris: Le Masque, 1934.

All articles Cryptogram

The cipher that has been sprouting the fantasies of many people in all its aspects for 90 years.

All articles La Buse

The life and work of the most famous French pirate of the 18th century.

All articles Backgrounds

Stories and history about the “Golden Era of Piracy”, La Buse and the cryptogram.