THE FRENCH ALPHABET

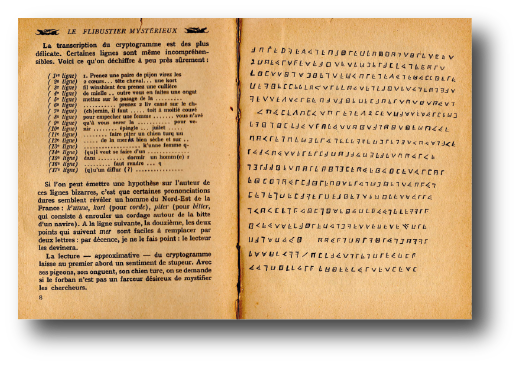

The question of which letters were officially introduced in the French alphabet and when is crucial for the dating of the cryptogram from the “Flibustier mystérieux”. The letter pairs I/J and U/V are particularly relevant here, as they were often treated as variants of one and the same letter until well into the 18th century. It was not until the 4th edition of the Académie française dictionary in 1762 that they were officially separated – J and V were recognized as independent letters. This development is reflected not only in official regulations, but also in printed matter of the time. The historical overview shows that the clear distinction in writing did not become common practice until the mid-18th century – a finding that also allows conclusions to be drawn about the possible date of origin of the cryptogram.

The following text was generated with the help of ChatGPT deep research (checked for correctness of content):

Practical use of V and U as well as I and J (ca. 1700-1750)

In French printed matter from the early to mid-18th century, the letter pairs V and U as well as I and J were not always treated as separate letters. Rather, the Latin tradition that V/U were merely two forms of one letter applied until then – as did I/J. In practice, this meant that a V was typically placed at the beginning of a word, while U was used within a word. For example, une (‘one’) was written as vne and vivre (‘to live’) as viure; hiver (‘winter’) appeared as yuer, and rêveur (‘dreamer’) as resueur. The situation was similar with I/J: a capitalized J was usually not distinguished from I, but was regarded as a decorated form of I. Accordingly, forms such as Iournal for journal and Ianuier for Janvier (January) can be found in printed documents of the time. For example, the first French journal in 1665 was entitled “Le Iournal des Sçavans”, with the J in Journal being printed as I and the U in Lundi as V (“Du lundy V. Ianvier 1665”). J was also replaced by I and U by V in names such as Jean (Iean) or Jacques (Iacques). This convention remained widespread in printed typesetting, so that a reader at the time had to read “IUSTICE” as Justice and “VNE FOIS” as une fois.

Comparison with the official alphabet of the Académie française

The official alphabet of the French language, as recorded in the dictionary of the Académie française, initially lagged behind printed practice. The first edition of the Dictionnaire de l’Académie (1694) was still strictly based on the traditional Latin alphabet and did not count any separate letters J or U/V. I stood for both i and j, and V for both v and i. I stood for both i and j, and V for both v and u. In the early editions of the dictionary, words with J were therefore classified under the letter I, and U and V were also regarded as one class. The Academy was initially conservative and etymologically motivated in this matter – they stuck to the old spelling, even if the spoken sounds no longer suggested this.

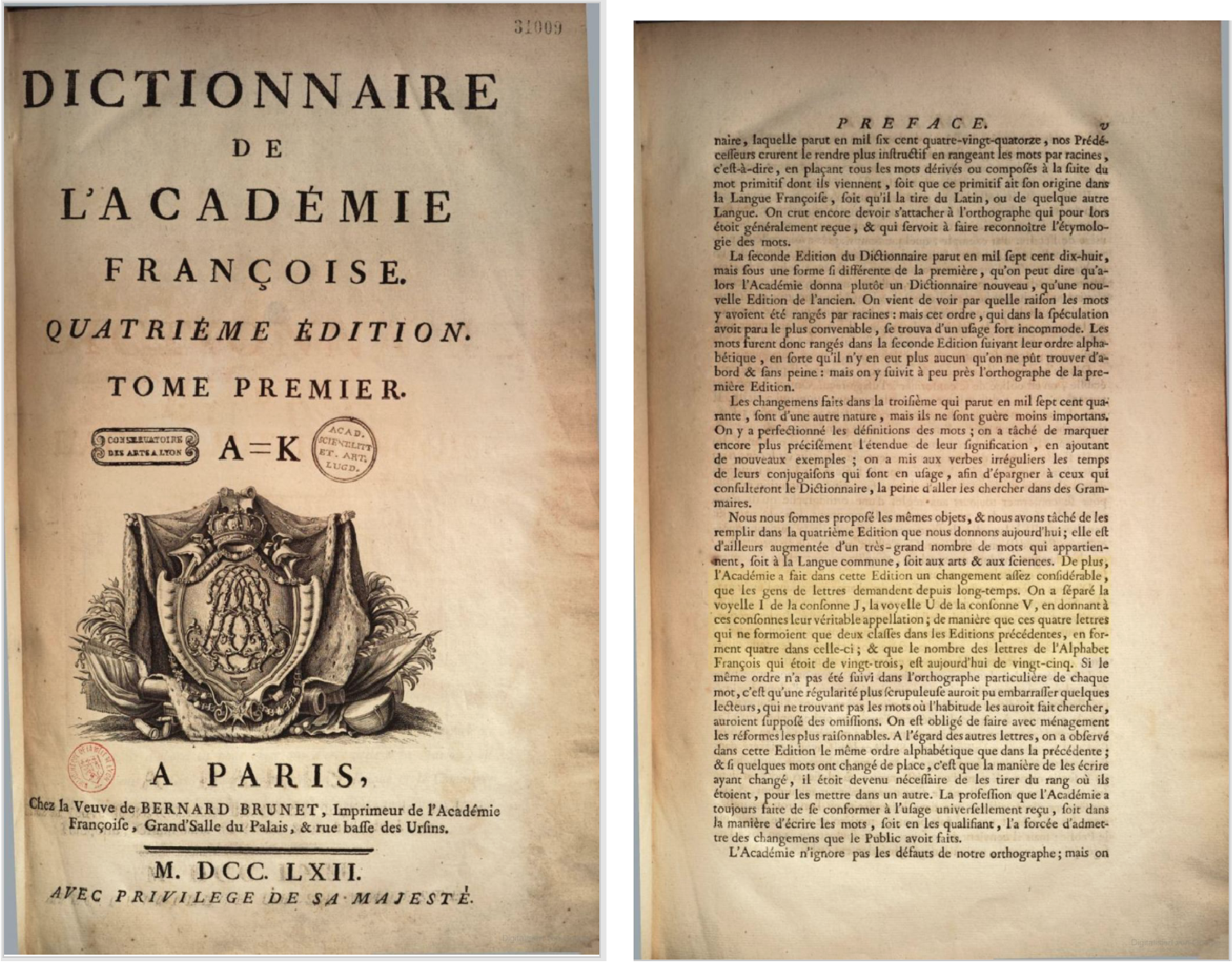

There was finally a formal alignment between the alphabet and usage in the middle of the 18th century. In the 4th edition of the Académie dictionary (1762), the letter pairs I/J and U/V were officially separated for the first time. The Académie now accepted the distinction between the vowel I and the consonant J as well as the vowel U and the consonant V. This increased the number of letters in the French alphabet from 23 to 25. J and U were given their own chapters in the dictionary.

Time of clear separation in practice

In practice, the clear separation of V/U and I/J gradually took place over the course of the 18th century. At the beginning of the century, the old custom was still frequently adhered to. Many books and newspapers continued to print I for today’s J or used V at the beginning of the word instead of U. However, some printers were already beginning to use J and U for better differentiation. A clearer distinction can be observed from the 1750s at the latest. New works were increasingly set with separate letters – such as J for the j sound and U for the u sound – as this made them easier to understand. The Académie française itself stated in 1762 that it was now bowing to the “generally established usage”. This shows that the separate spelling was already widespread at this time.

However, the transition was fluid. Even in the first half of the 18th century, there were still many mixed forms. One well-known example is the writer Voltaire: his pseudonym is derived from an anagram of Arouet le jeune, which only worked because I = J and U = V were considered the same. Such cases show that the separation was not universal before the 1750s. From 1762 onwards, the official dictionary also adhered to the new standard, and the older alternate usage increasingly disappeared.

“Moreover, in this edition the Academy has made a rather significant change, which scholars have long been calling for. The vowel I has been separated from the consonant J, the vowel U from the consonant V, by giving these consonants their true designation; so that these four letters, which formed only two classes in the previous editions, form four in this edition; & that the number of letters of the French alphabet has increased from twenty-three to twenty-five.”

Official proposals and introduction of separation

As early as the 16th century, language reformers recognized the need to distinguish the consonant J from the vowel I. In 1545, Louis Meigret suggested representing the consonantal i sound with a special sign, later called “i long”. Other European scholars such as Trissino and Nebrija also introduced J and U as separate letters in their languages at the time. In France, Jacques Peletier du Mans and Pierre de La Ramée (Ramus) called for the separation in phonetically motivated orthographic proposals. These new characters were later called lettres ramistes.

An important practical step was the typographic design of a separate capital letter U by the printer Lazare Zetzner in 1629. The Académie française also took up the idea of separation later on. From 1663, the poet Pierre Corneille campaigned for the Academy to officially recognize J (and V). Although this initially had no effect, it was an important impulse.

The final official introduction took place with the 4th edition of the dictionary in 1762 (see above). This increased the number of letters to 25, whereas the letter W had to wait until the 20th century to complete the French alphabet as the 26th letter.

The significance of this information for the cryptogram and its alleged author can be found in the article “The end of a legend”.

Sources mentioned:

– Académie française. Dictionnaire de l’Académie françoise. 4th edition, Paris: Bernard Brunet, 1762.

– Académie française. “Préface de la quatrième édition (1762)”.

All articles Cryptogram

The cipher that has been sprouting the fantasies of many people in all its aspects for 90 years.

All articles La Buse

The life and work of the most famous French pirate of the 18th century.

All articles Backgrounds

Stories and history about the “Golden Era of Piracy”, La Buse and the cryptogram.