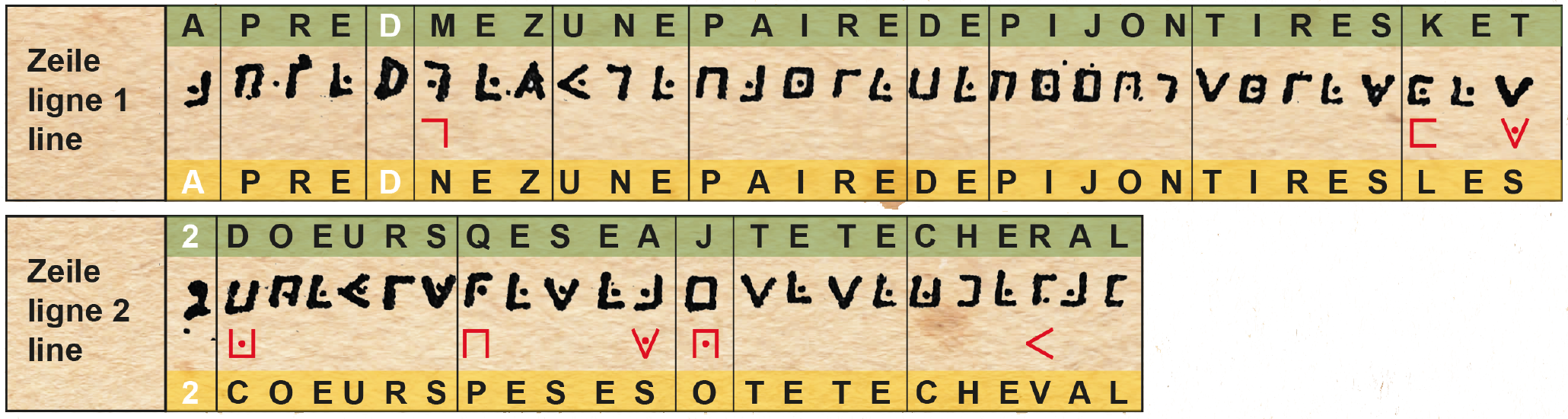

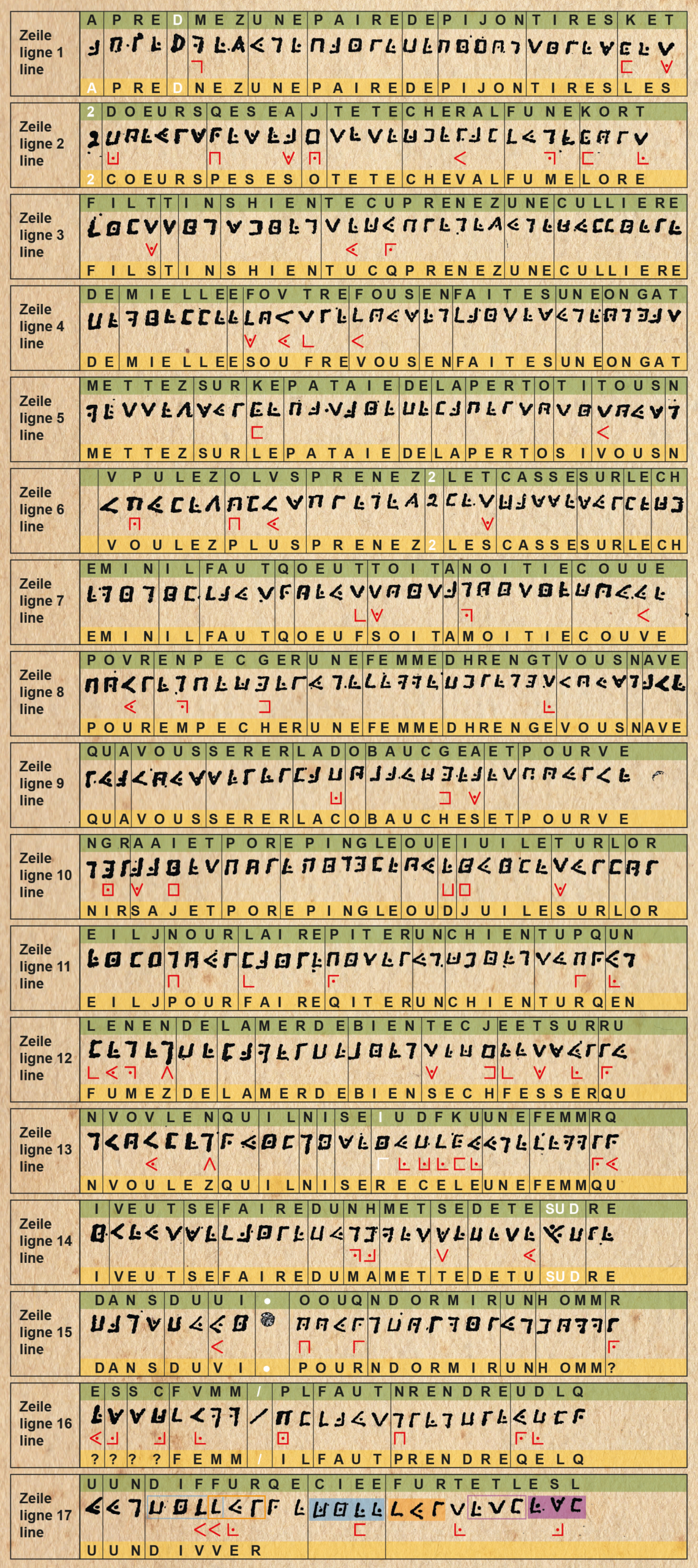

THE NEW TRANSCRIPTION

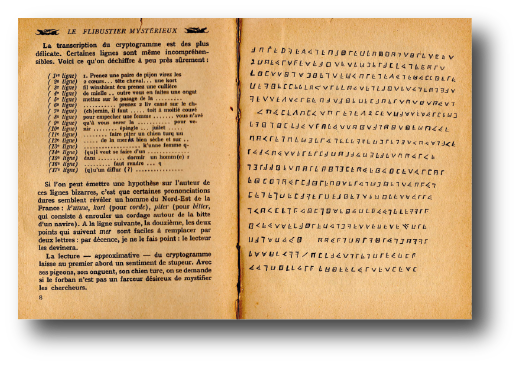

For the first time since the publication of the cryptogram in 1934, this new transcription provides a consistent and systematically comprehensible attempt at interpretation. It is not based on a new theory of the content, but on a structured analysis of the scribal errors present in the text. Based on typical errors in the use of the Freemason code – such as transposed dots or lines – as well as phonological and orthographic peculiarities, the text was cleaned up section by section and converted into modern French. For the most part, the resulting sentences provide historical recipes, medical applications and cultural references that can be located in historical sources from the 16th to 18th centuries. The error logic proposed here thus offers a realistic approach to giving the content of the document a concrete meaning for the first time.

The pigeons

Original transcription:

APREDMEZUNEPAIREDEPIJONTIRESKET

2DOEURSQESEAJTETECHERAL

Cleanup:

PRENEZ UNE PAIRE DE PIJON

TIRES LES COEURS PESES O TETE CHEVAL

Modern inscription:

Prenez une paire de pigeons. Tirez les coeurs, pressez[-les] à la tête du cheval.

Translation:

Take a pair of pigeons. Pull out the hearts and press them against the horse’s head.

Linguistic notes:

The writer uses -es twice instead of -ez (command form), which is phonologically identical. He is probably confusing the two similar verbs peser and presser (= to press).

Estimated reliability of the transcription: 85%

Comment:

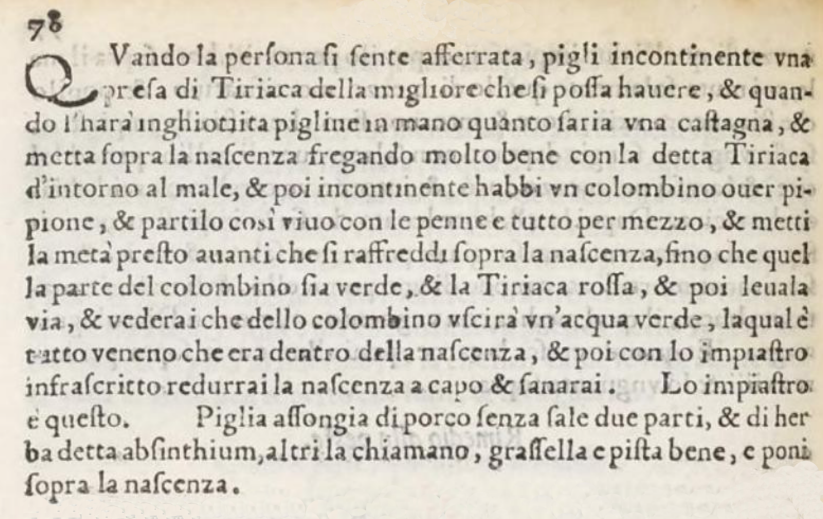

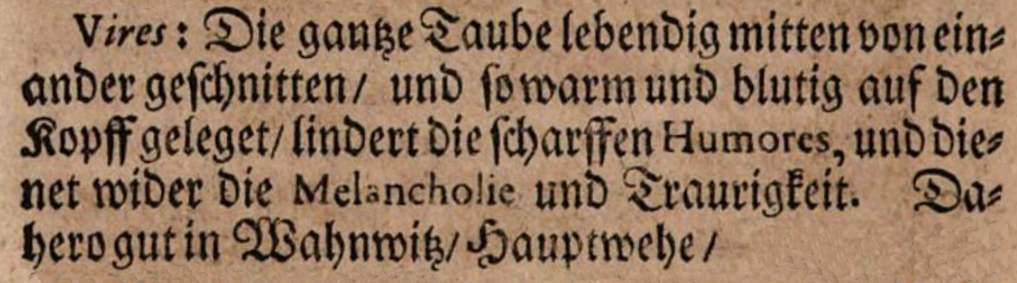

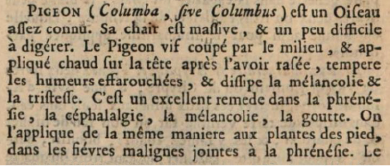

The recipe for halving pigeons alive has been used by a number of authors since the 16th century at the latest

. Girolamo Ruscelli listed it as a remedy against the plague as early as 1557 in his 6-volume work “De secreti del reverendo donno Alessio Piemontese”. There is no evidence that it was also used to treat horses. In later sources, the recipe is mainly recommended against mental illnesses such as melancholy

.

Girolamo Ruscelli (“Vicenti Busdrago”): De’Secreti del reverendo donno Alessio Piemontese 1557, prima parte, p. 78

L. Christoph Hellwig: Lexicon pharmaceuticum, Erfurt 1714, p. 46

Nicolas Alexandre: Dictionnaire botanique et pharmaceutique, Paris 1759, p. 418

Richard Brookes (M.D.): Natural History of Birds, London 1763, p. 177

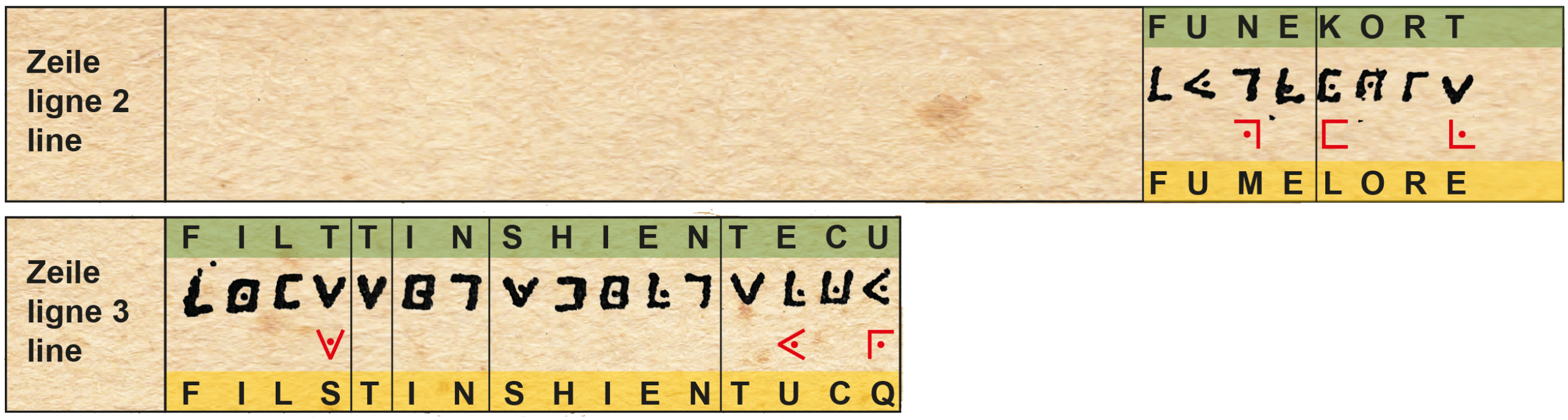

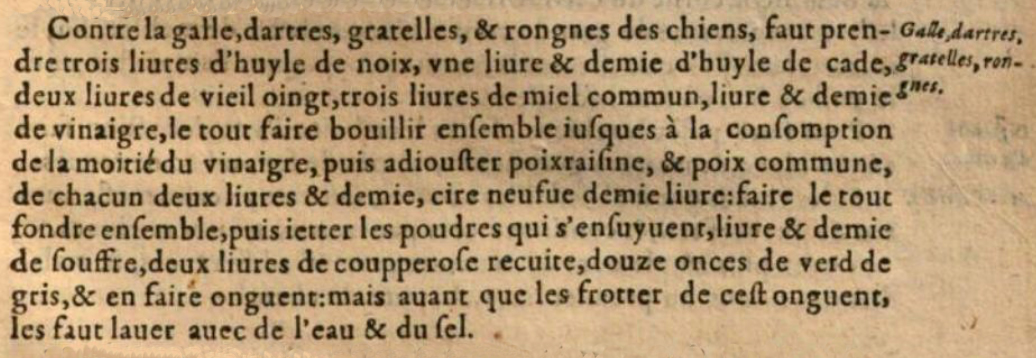

The smoke enema

Original transcription:

FUNEKORT

FILTTINSHIENTECU

Cleanup:

FUME L OREFILS T IN SHIEN TUCQ

Modern inscription:

Fumez l’orifice d’un chien turc.

Translation:

Make a smoke enema for a mangy dog.

Linguistic notes:

As in many other places, the text is written phonologically. The z at the end of Fume is missing, orefils is written instead of orifice. Instead of un, the similarly pronounced in is used.

Estimated reliability of the transcription: 90%

Comment:

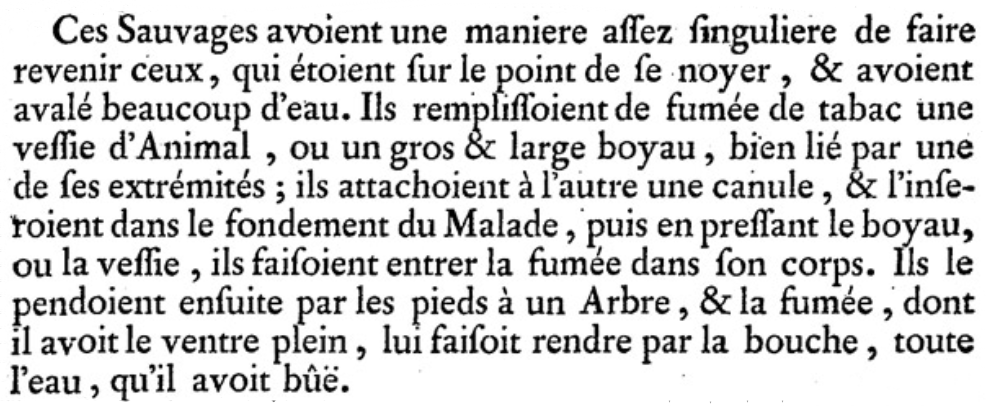

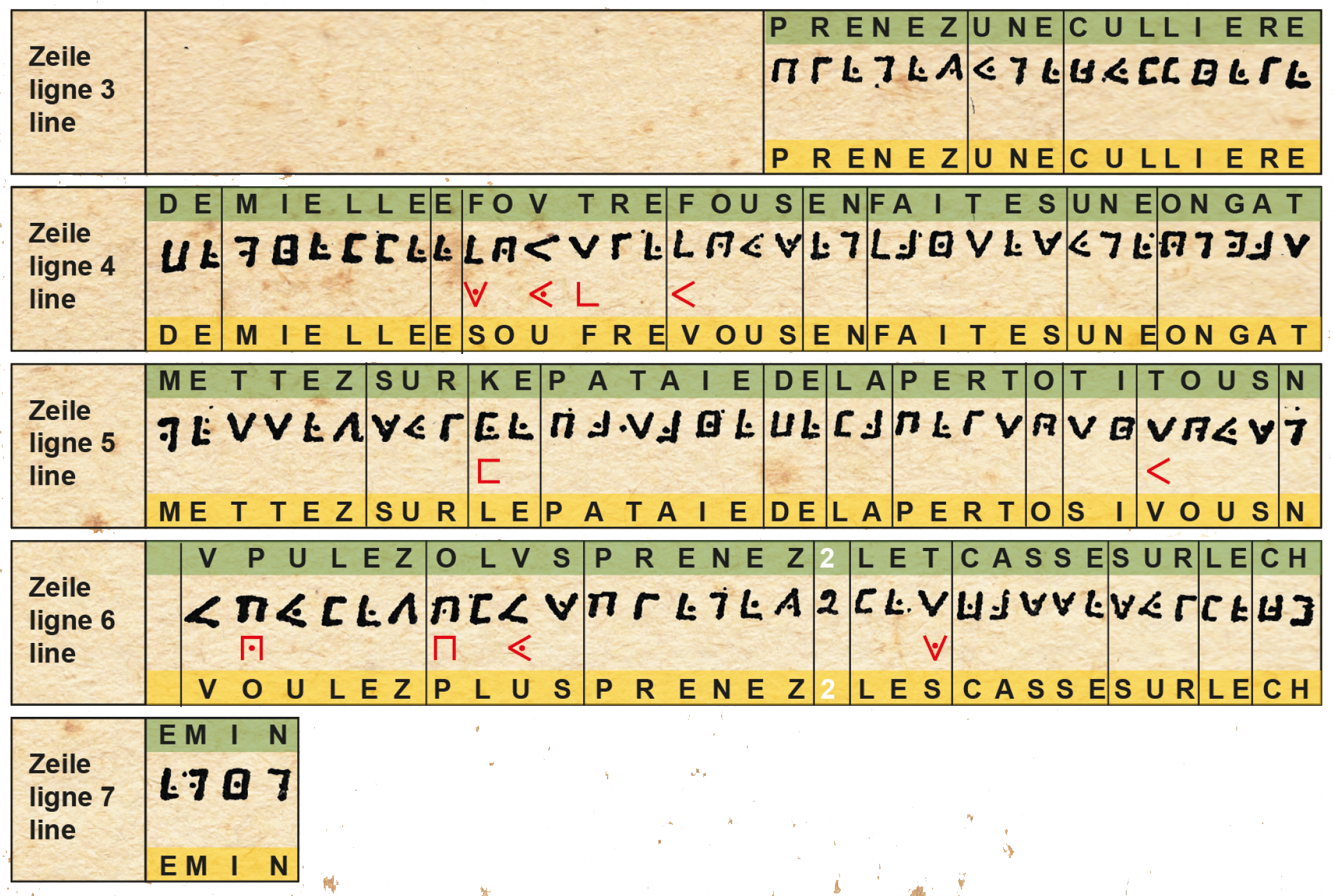

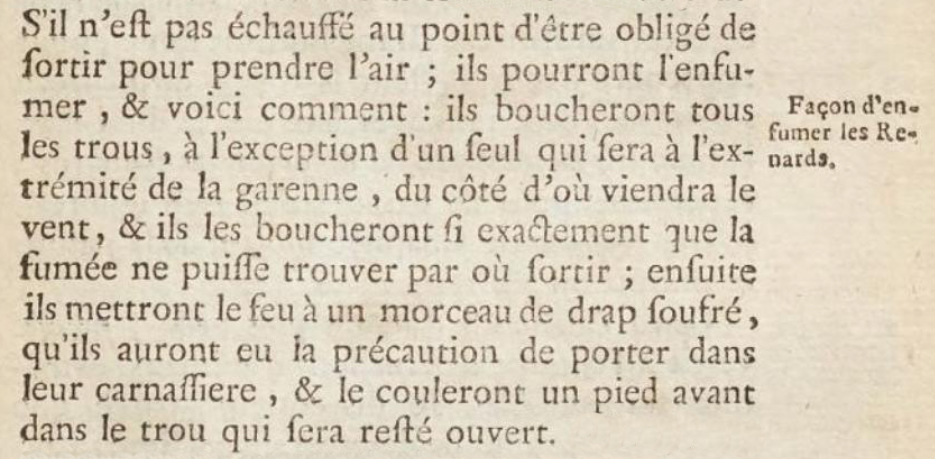

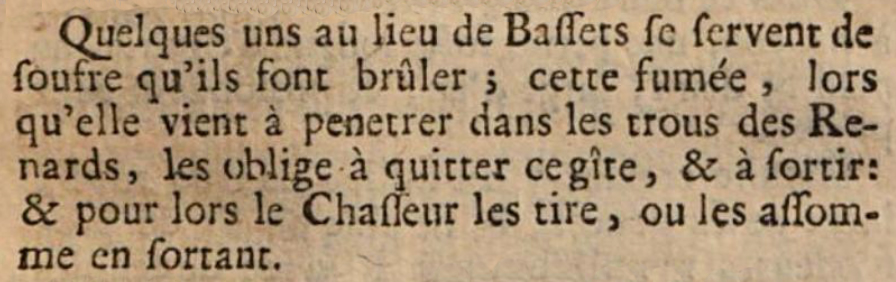

The term chien turc probably refers to the Egyptian or African naked dog, which is practically completely hairless and is now considered extinct. In a figurative sense, the writer is most likely referring to a mangy dog (see also the section “The mangy dog”).

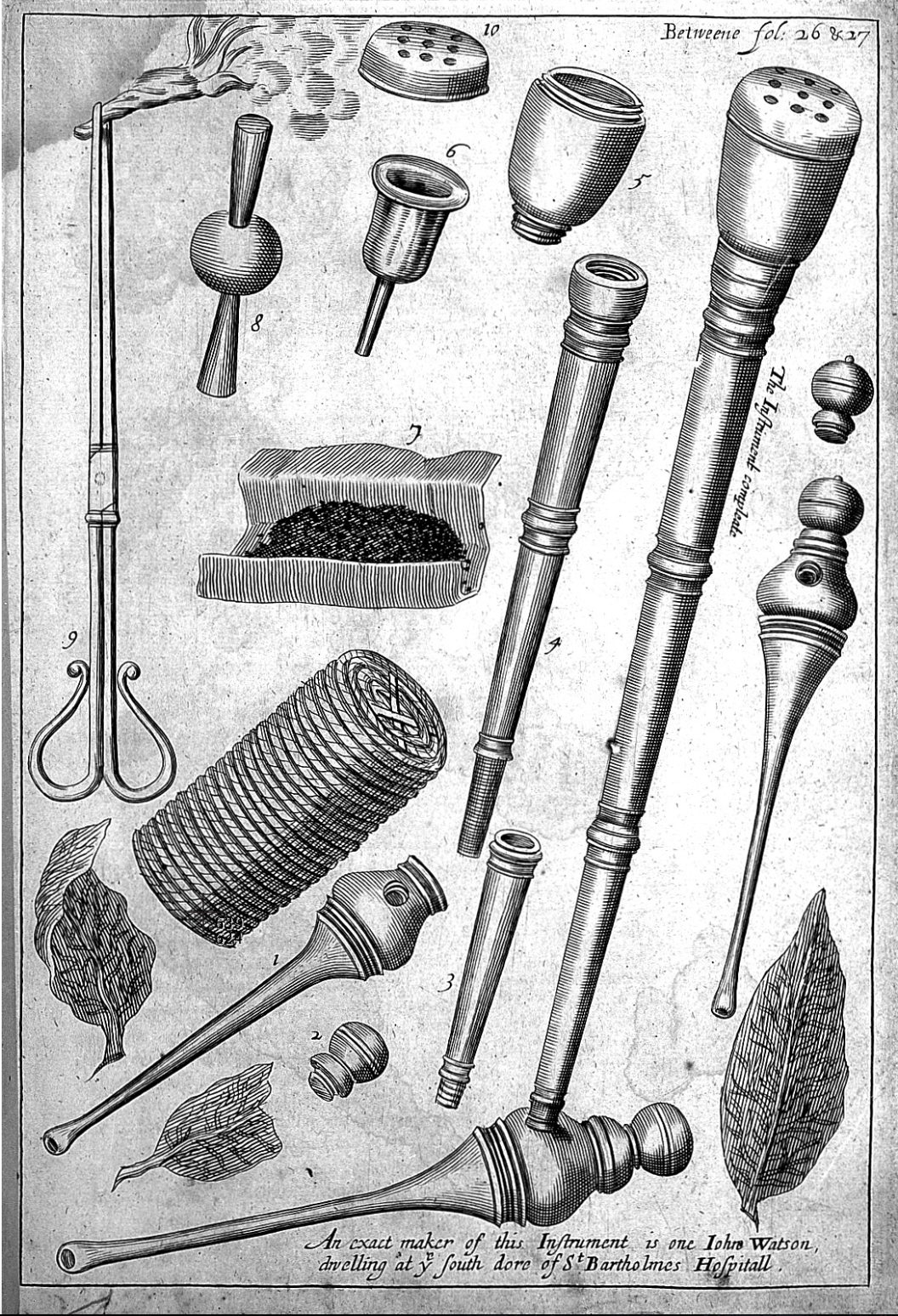

From the end of the 17th century until the early 19th century, blowing tobacco smoke into the anus was a common method of bringing drowned people back to life. Smoke enemas were also used to treat constipation, colic or worm infestations. There are no sources that would prove that dogs were also treated with it.

Gardanne JJ. Recherches sur la mort des noyés et des moyens d’y remédier. In : Observations sur la physique, sur l’histoire naturelle et les arts, 1787

Woodall J. The Surgeon’s Mate, 2°ed, R. Young for N. Bourne, London, 1639

First description of a smoke enema from Canada by Lescarbot (Nouvelle France), 1611, reprinted in: Charlevoix PFX. Histoire et description générale de la Nouvelle France, 1744

Journal des savants, Volume 75, 1749

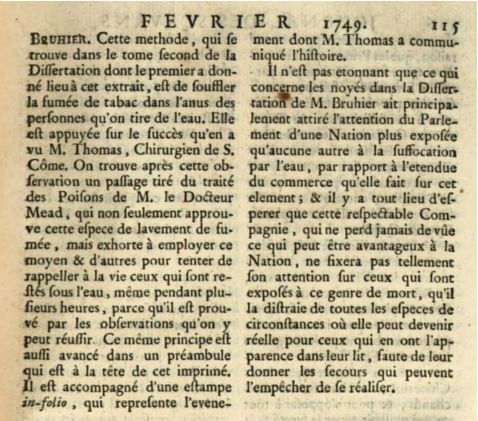

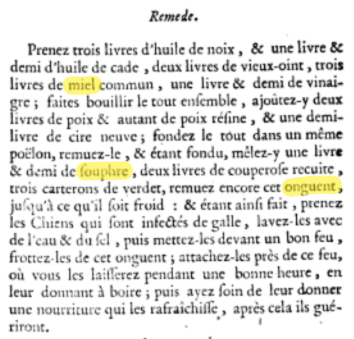

The mangy dog

Original transcription:

PRENEZUNECULLIERE

DEMIELLEEFOVTREFOUSENFAITESUNEONGAT

METTEZSURKEPATAIEDELAPERTOTITOUSN

VPULEZOLVSPRENEZ2LETCASSESURLECH

EMIN

Adjustment:

PRENEZ UNE CULLIERE DE MIELLE E SOUFRE, VOUS EN FAITES UNE ONGAT.

METTEZ SUR LE PATAIE DE LA PERT O SI VOUS N VOULEZ PLUS PRENEZ

LES CASSE SUR LE CHEMIN

Modern transcription:

Prenez une cuillère de miel et [de] soufre, vous en faites un onguent. Mettez [-le] sur la patée de la bête, ou si vous ne [la] voulez plus, prenez des casses sur le chemin.

Translation:

Take a spoonful of honey and sulphur and make an ointment. Put it on the animal’s food mash, or if they no longer want it, take laburnum from the path.

Linguistic notes:

In addition to some phonological spelling mistakes(ongat instead of onguent, pataie instead of patée, pert instead of bête), there are also orthographic errors: culliere instead of cuillère, mielle instead of miel, les casse instead of les casses.

Estimated reliability of the transcription: 70%

Comment:

The theory of the mangy dog (see “The smoke enema”) is confirmed in this section: sulphur ointment is still used today as a remedy for mange and scabies. The method of preparation described is a reduced version of recipes that can be found in various authors since the middle of the 16th century. What is confusing is that the writer recommends adding the ointment to the animal’s food. Sulphur ointment is normally applied to the affected skin.

The second part of the passage is also not easy to interpret. The term “les casses” certainly refers to Cassia fistula (English: golden shower). Cassia is used as a laxative. The combination of the two parts of the passage suggests that cassia could be used to get rid of the animal. It is unlikely that this would work with a laxative. Could it be that the two parts do not belong together at all? Does “si vous ne voulez plus” perhaps mean: if they no longer want to be constipated?

Chien turc. Georges Louis Leclerc de Buffon (1707-1788), Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière, 1789 (after illustration by Jacques de Sève, 1755).

Cassia fistula. Johann Wilhelm Weinmann: Phytanthoza-Iconographia, 1739

Jacques Roussin: L’agriculture, et maison rustique de M. Charles Estienne, 1594

Noël Chomel: Dictionnaire economique, 1741

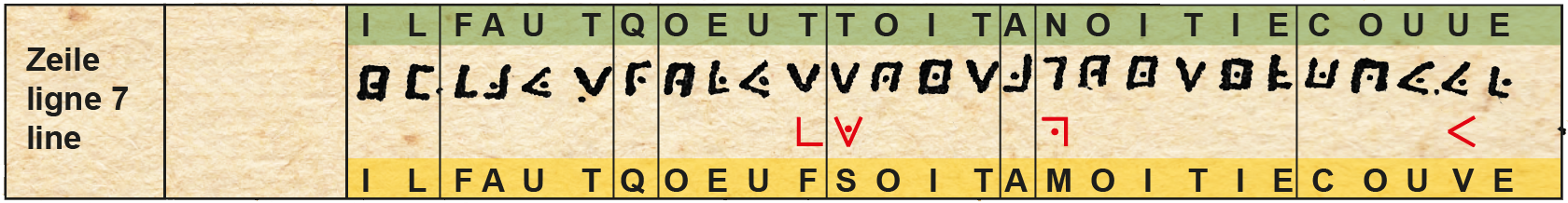

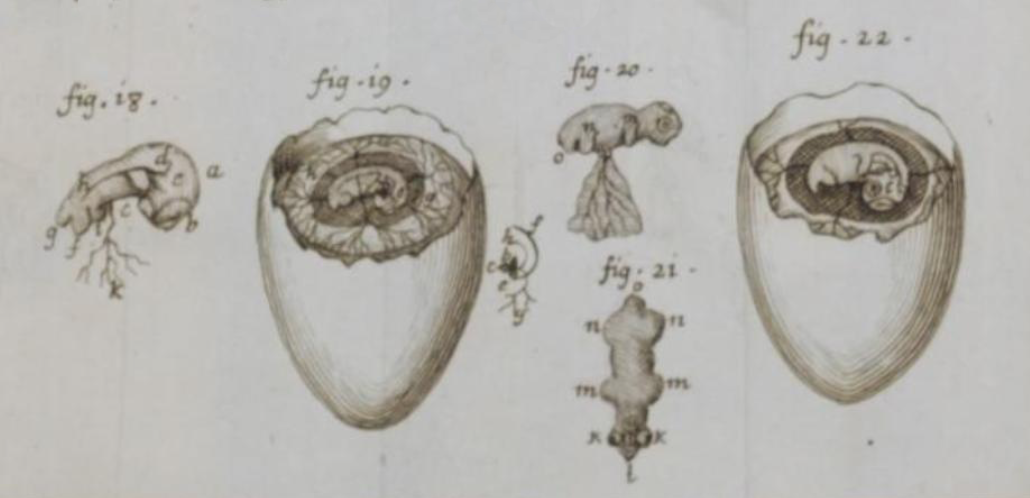

The egg

Original transcription:

ILFAUTQOEUTTOITANOITIECOUUE

Adjustment:

IL FAUT Q OEUF SOIT A MOITIE COUVE

Modern inscription:

Il faut que [l’] oeuf soit à moitié couvé.

Translation:

It is necessary for the egg to be half-hatched.

Linguistic notes:

couue (= couvé) possibly shows the equation of U and V, which was still common in the last quarter of the 18th century, at least in the official French alphabet.

Estimated reliability of the transcription: 95%

Comment:

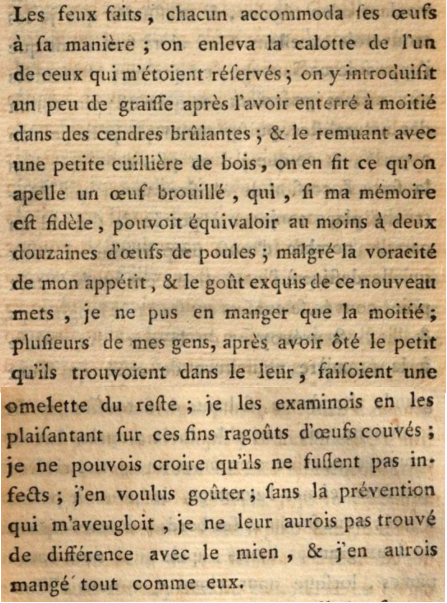

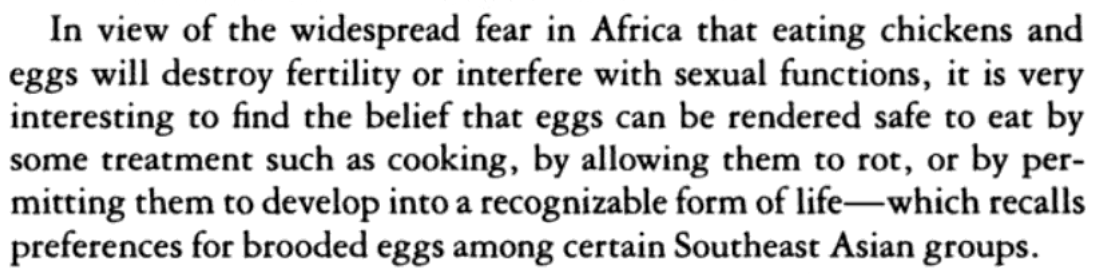

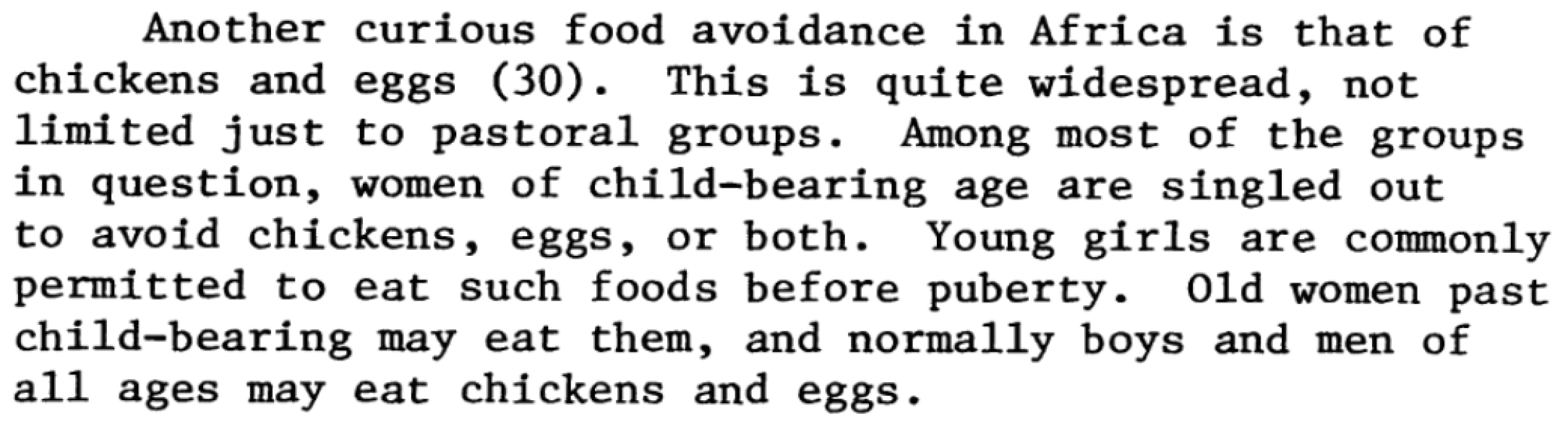

Il faut que denotes a must, a rule in French. But what rule can be constructed or derived from the half-incubated egg? Research shows that an egg taboo still prevails in large parts of Africa to this day. Women of childbearing age and children in particular were and are not allowed to eat eggs and chicken meat. In 1790, the African traveler François Le Vaillant reported how his African companions prepared a scrambled egg with incubated eggs during an open-air meal.

Anthropologist Frederick J. Simoons wrote about the African egg taboo in 1967: “… it is very interesting to find the idea that eggs can be made safe to eat by subjecting them to certain treatments such as boiling, allowing them to rot, or allowing them to develop into a recognizable form of life …”

The interpretation of the passage could therefore be: To be allowed to eat an egg, it must be half-hatched.

Is this sentence in the cryptogram a reference to a possible African origin of the writer?

Voyage de M. Le Vaillant dans l’intérieur de l’Afrique, Tomme 2, 1790, p. 247f.

Simoons, Frederick J.: Eat Not this Flesh: Food Avoidances from Prehistory to the Present, 1994

Jean-Jaques Scheuchzer: Physique sacrée, ou Histoire-naturelle de la Bible, 1732

Balut is a cooked duck or chicken egg that is consumed as a food, especially in the Philippines, Vietnam and Cambodia.

D. Walcher: Food, Man, and Society, 2012, p. 36

BOLAKONGA Bobwo, LES TABOUS DE LA GROSSESSE CHEZ LES FEMMES SAKATA (ZAIRE), 1989, p. 43

E. Z. Gadagbe: Conseils de santé à la famille africaine, 1977, p. 121

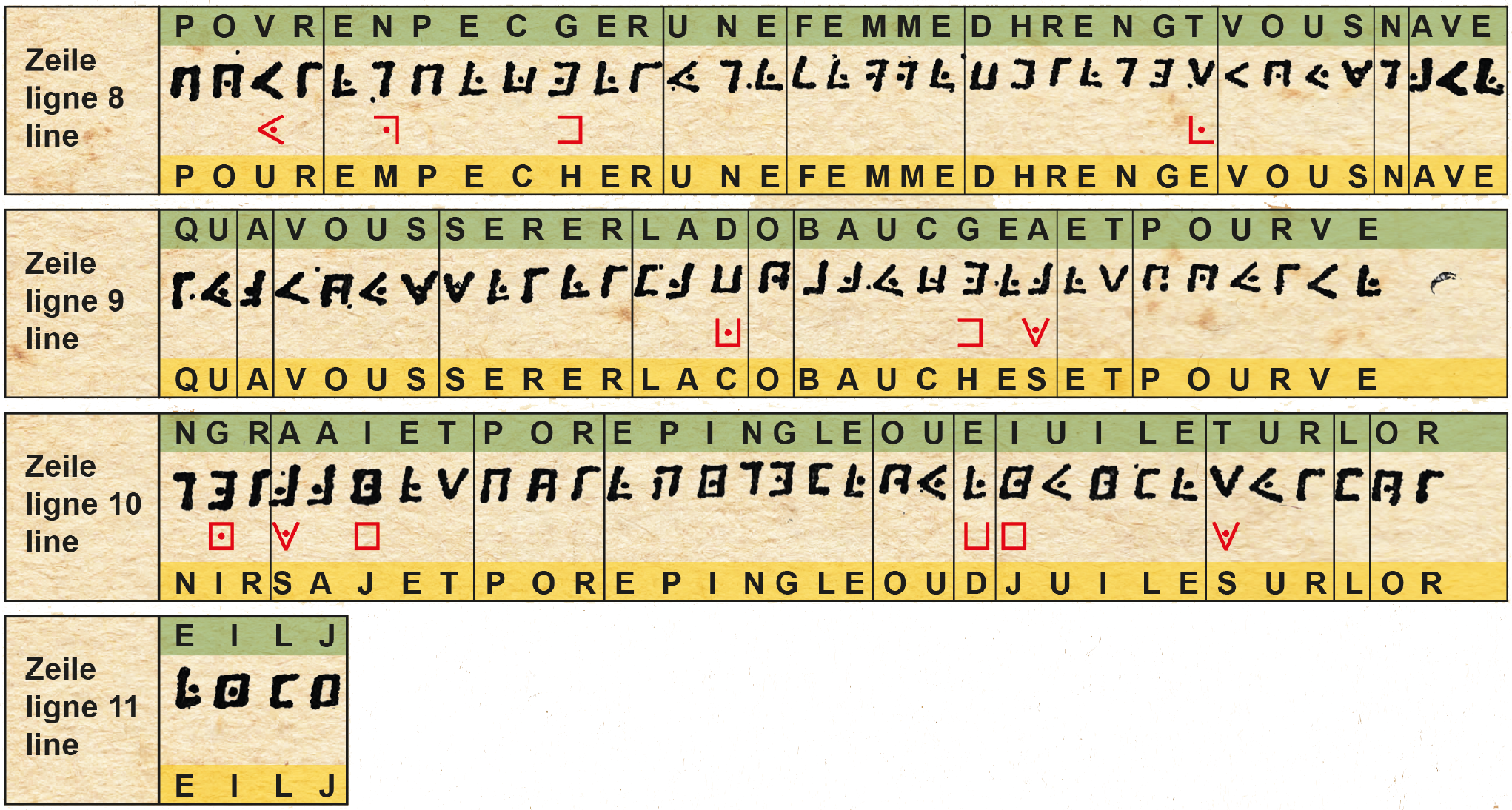

Bad breath

Original transcription:

POVRENPECGERUNEFEMMEDHRENGTVOUSNAVE

QUAVOUSSERERLADOBAUCGEAETPOURVE

NGRAAIETPOREPINGLEOUEIUILETURLOR

EILJ

Correction:

POUR EMPECHER UNE FEMME DHRENGE VOUS N AVE QU A VOUS SERER LAC O BAUCHES

ET POURVENIR SAJET POR EPINGLE OU D JUILE SUR L OREILJ

Modern inscription:

Pour empêcher une femme dérangée, vous n’avez qu’à serrer [de la gomme] laque contre la bouche et obtenir un sachet de clous [de girofle] ou mettre de l’huile [de girofle] sur l’oreiller.

Translation:

To prevent a woman from being disturbed [by bad breath], press shellac on her mouth and get a bag of cloves or drip oil on the pillow.

Linguistic notes:

Phonological errors: Dhrenge instead of dérangée, bauches instead of bouches, oreilj instead of oreiller.

Confusion of words: Pourvenir instead of obtenir, épingle instead of clou (in German Nadel instead of Nagel).

Serrer les dents means to grit your teeth. The writer has probably mixed up two meanings here.

Estimated reliability of the transcription: 70%

Comment:

Lac refers to lacca or gomme laque (= shellac). Its use against bad breath (especially as a result of scurvy) is documented several times by sources. Cloves and clove oil were valued for their intense fragrance. The use of sachets is also documented.

J. Pass : Clove tree (Syzygium aromaticum), 1808

Nicolas Alexandre: Dictionnaire botanique et pharmaceutique, 1759

Georg Franck von Franckenau: Flora Francica Aucta, or Complete Herbal Lexicon, 1766

John “of” Cuba: Le iardin de sante, 1539

Noël Chomel: Dictionnaire oeconomique, 1740

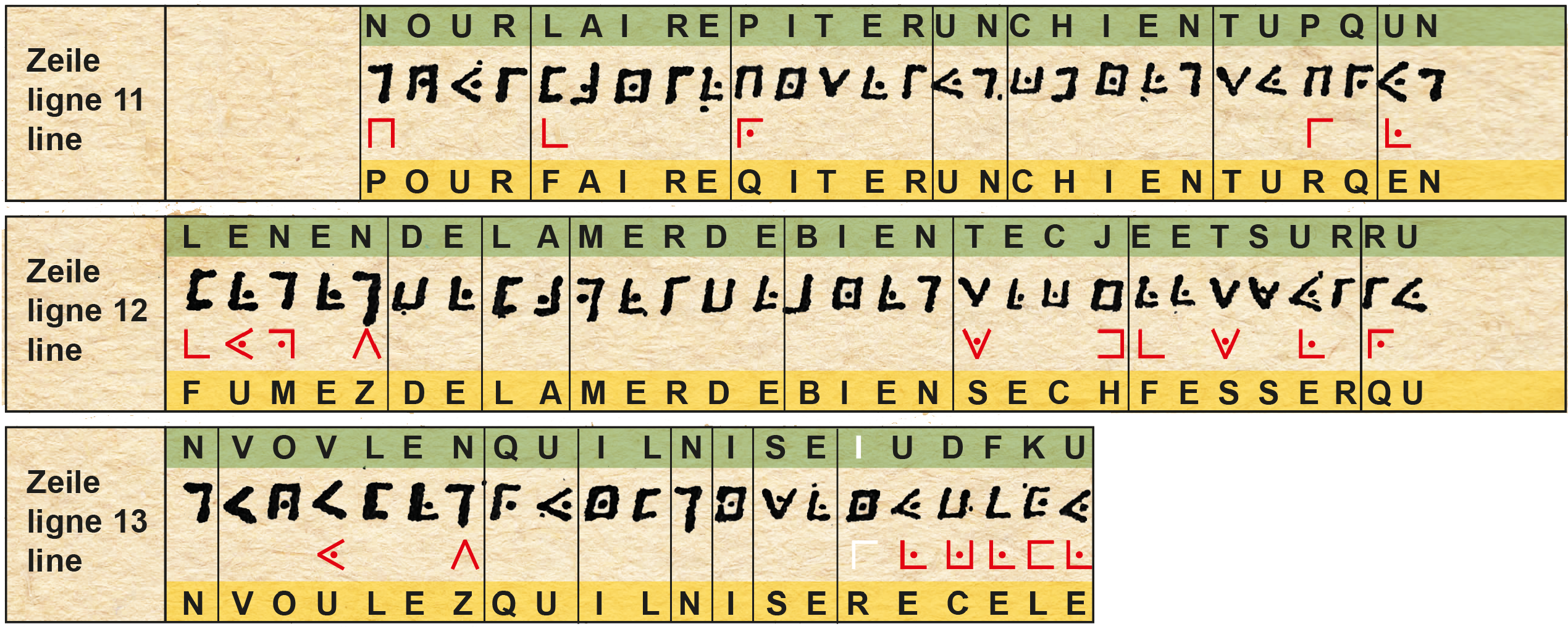

Fumigation

Original transcription:

NOURLAIREPITERUNCHIENTUPQUN

LENENDELAMERDEBIENTECJEETSURRU

NVOVLENQUILNISEIUDFKU

Clean-up

POUR FAIRE QITER UN CHIEN TURQ

ENFUMEZ DE LA MERDE BIEN SECH

FESSER QU N VOULEZ QU IL N I SE RECELE

Modern transcription:

Pour faire à qu’un chien turc quitte [l’endroit] enfumez de la merde bien sèche. Fessez [-le], si [vous] ne voulez [pas] qu’il s’y cache.

Translation:

To drive away a mangy dog, burn dried shit. Give him a kick in the butt if you don’t want him to hide.

Linguistic notes:

In this section, three words have undergone a major change: enfumez (from unlenen), fesser (from eetsur) and recele (from iudfku). With one exception (i to r in recele), however, they can all be explained by the error logic.

Receler cannot be used reflexively in French. It can therefore be assumed that there is confusion with (se) cacher.

Estimated reliability of the transcription: 70%

Comment:

This section cannot be substantiated by any historical, biological or other concrete sources. The process described is reminiscent of fumigation during fox hunting. There is some evidence (e.g. from beekeeping) that the burning of animal excrement for fumigation was practised.

Jan van der Straet, called Stradanus, 1578

Albrecht Dürer, The Flagellation, 1497 (detail with mangy dog)

Jean Baptiste Jacques LE VERRIER DE LA CONTERIE : L’École de la chasse aux chiens courans, 1778

Nicolas de Bonnefons: Delices de la campagne ou les ruses de la chasse et det de la pesche, 1732

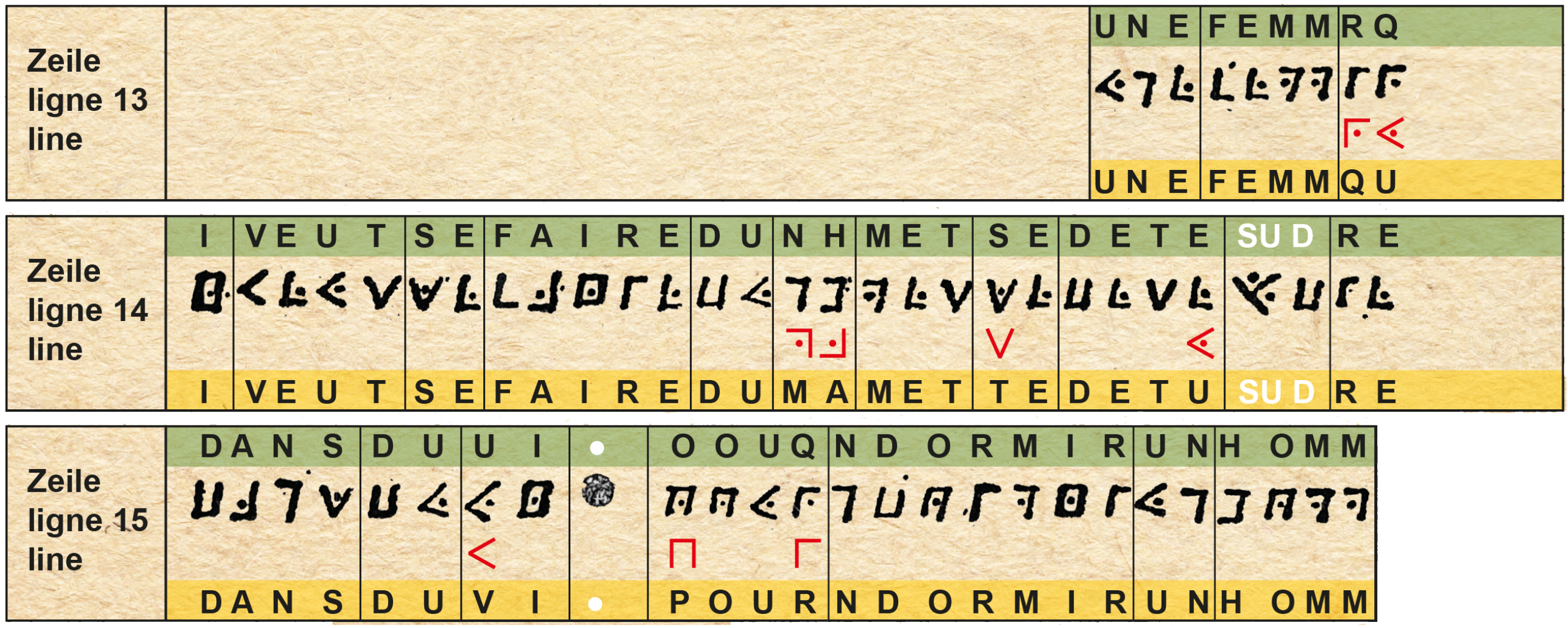

The unfaithful wife

Original transcription:

UNEFEMMRQ

IVEUTSEFAIREDUNHMETSEDETESUDRE

DANSDUUI●OOUQNDORMIRUNHOMM

Clean-up

UNE FEMM QUI VEUT SE FAIRE DU MA

MET TE DETURE DANS DU VI POUR NDORMIR UN HOMM

Modern inscription:

Une femme qui veut se faire du mal met de [la] dature dans du vin pour endormir un homme.

Translation:

A woman who wants to do bad things to herself mixes datura in the wine to put a man to sleep.

Linguistic notes:

The transcription from nh to ma is the only sensible option. Ma would then be a phonologically explainable form of mal. It is similar with ui to vin. U and v are equated (as with couue = couvé).

Estimated reliability of the transcription: 75%

Comment:

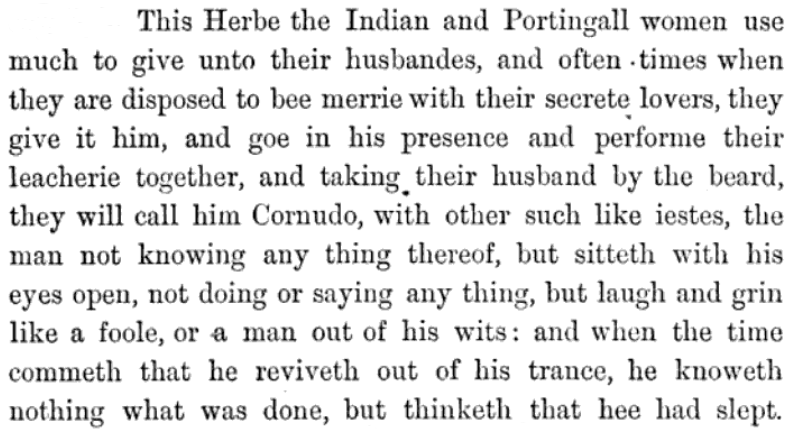

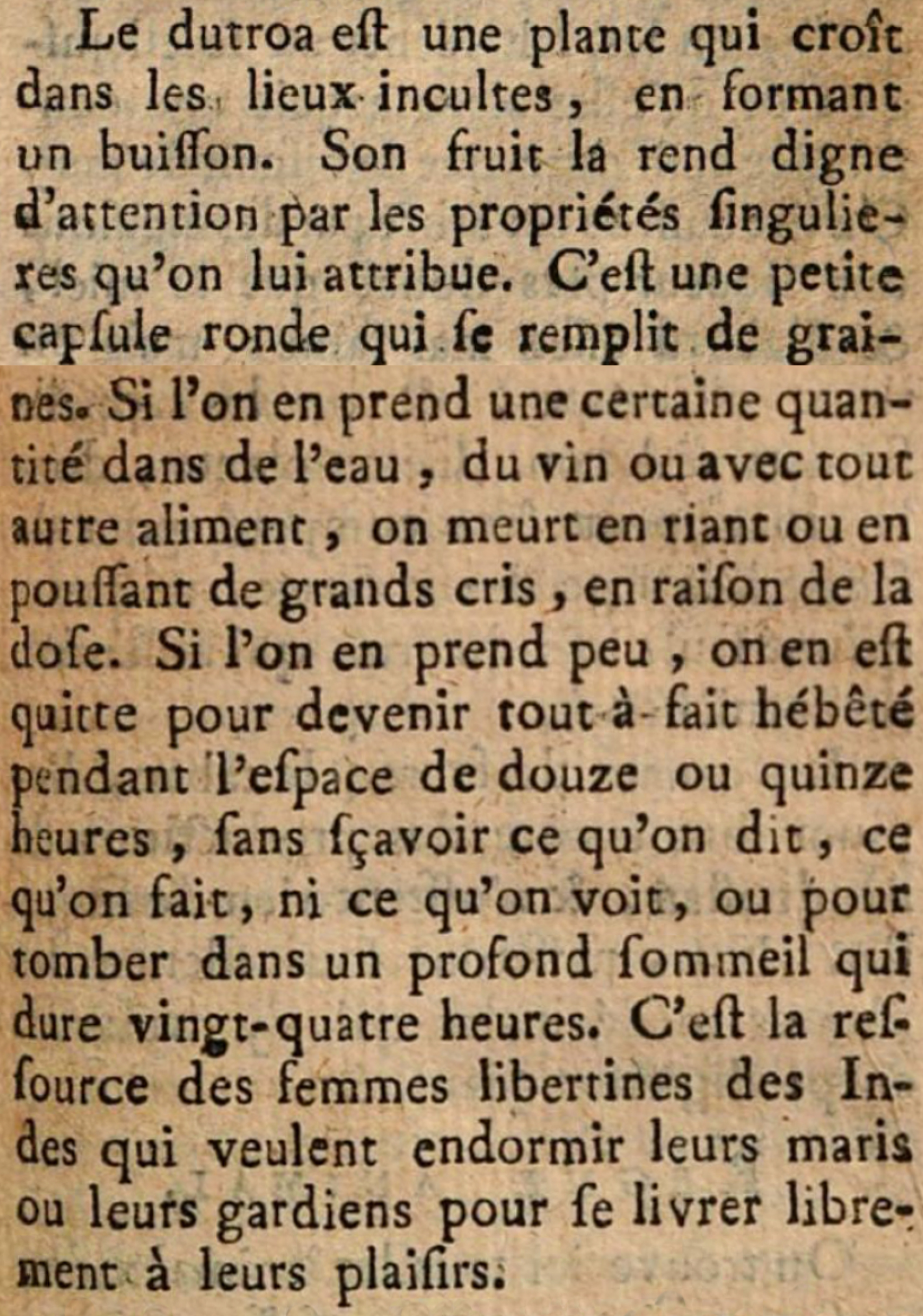

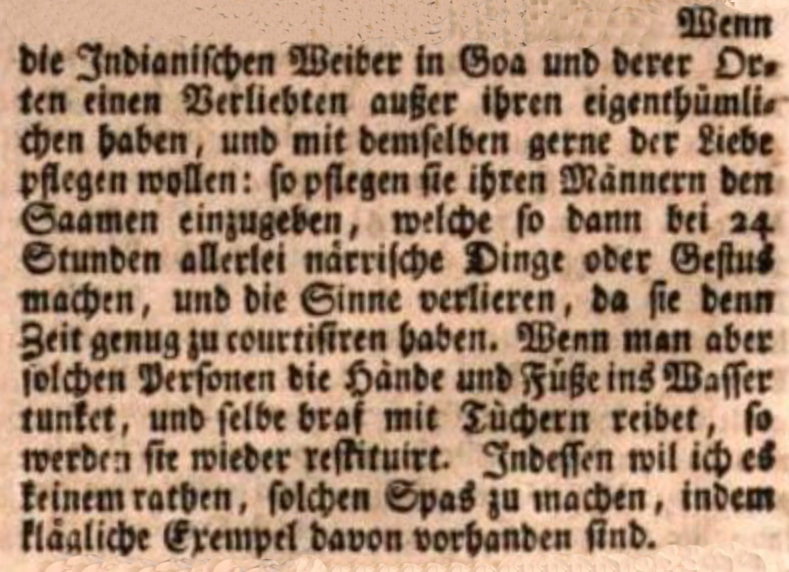

Datura (also Dutroa, Dutra, Dature, etc.) is the name of the datura(Datura stramonium). It was (and is) used as an intoxicant to alter consciousness. As early as 1585, Cristóbal Acosta described the abuse of the plant by women in love. Linschoten (1596) speaks of Indian and Portuguese women, later authors of women from Goa (India) who drugged their husbands in order to have fun with their lovers.

Peter van der Aa: A lady and gentleman of Goa, 1725

Stramonium malabaricum (datura). Giorgio Bonelli: ‘Hortus Romanus’, 1772

The Voyage of John Huyghen Van Linschoten to the East Indies (From the Old English Translation of 1598), 1885

Mélanges intéressant et curieux, 1766

Cristóbal Acosta: Trattato di Christoforo Acosta, 1585

A. C. Ernsting: Nucleus Totius Medicinae, 1770

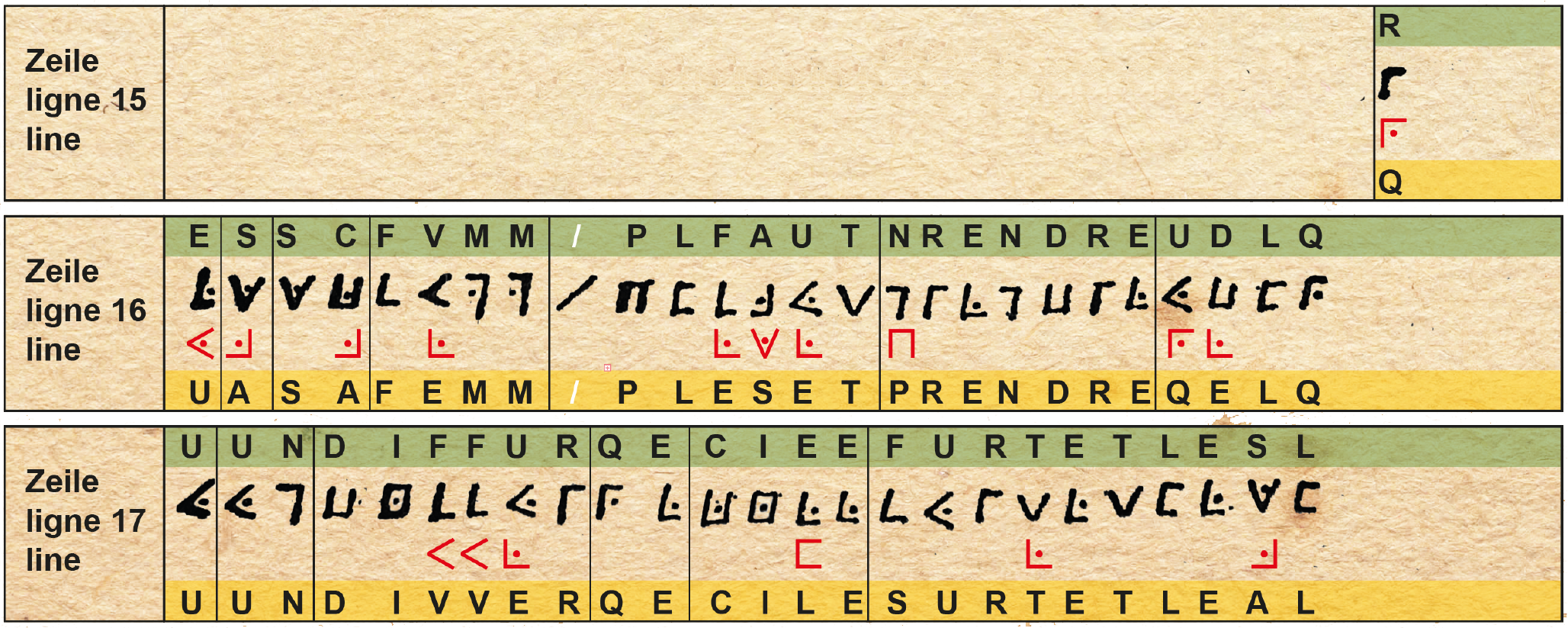

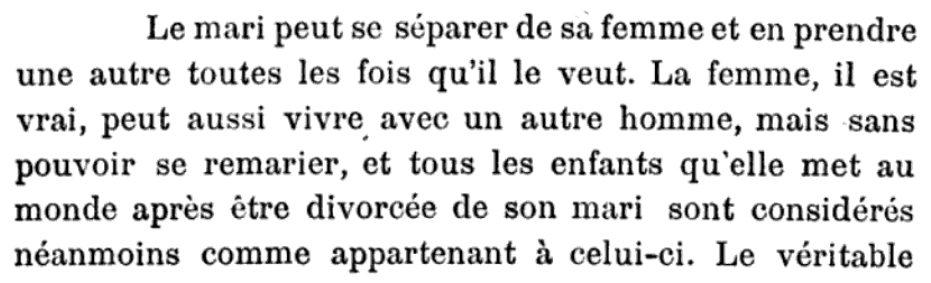

Unclear end

Original transcription:

R

ESSCFVMM/PLFAUTNRENDREUDLQ

UUNDIFFURQECIEEFURTETLESL

Adjustment

QU A SA FEMM PLESET PRENDRE QELQU UN DIVVER

QE C IL E SURE ET LEAL

Modern transcription:

Qu’il plaisait à sa femme [de] prendre quelqu’un d’autre que s’il était sûr et loyal.

Translation:

That it pleases his wife to take another, but only if he is reliable and faithful.

Linguistic notes:

Various parts of the transcription are unclear here. PLFAUT seems to be closer to il faut than to pleset. However, P to I cannot be reconciled with the error logic. The transcription of diffur to divver is just as dubious as lesl to leal. The word leal (= faithful) is last attested at the beginning of the 17th century.

Estimated reliability of the transcription: 30-50%

Comment:

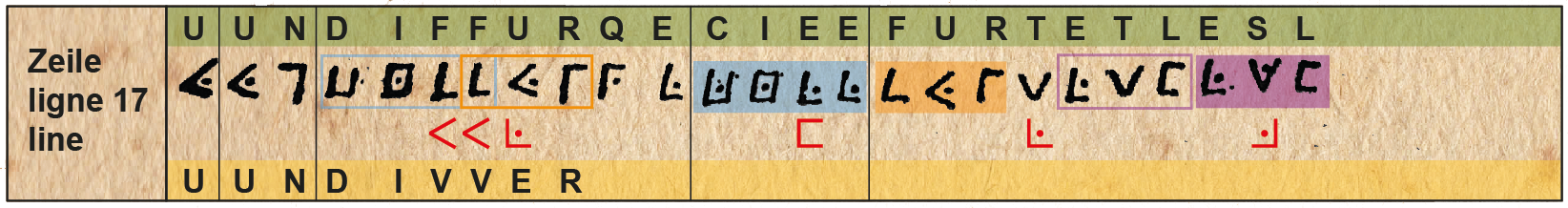

Does this part still belong to the “unfaithful wife” or is the topic being revisited here? Various authors of the 19th century point out that in Madagascar both men and women are allowed to take other partners. The following statement about the Sakalava people can be found on the page of “Le mouvement matricien”, referring to the time around 1700:

“Sakalava society is matriarchal and polygamous. The men may have several wives, the women several husbands”.

However, the sentence in the cryptogram is too vague; a connection with Madagascar is purely speculative.

Madagascan wedding (unknown origin)

Alfred Grandidier: Histoire physique, naturelle, et politique de Madagascar, 1885

Ida Pfeiffer: Voyage a Madagascar, 1881

Femme sakalava (J. Rousselet, 1902)

Too little text?

It is noticeable that at the end of the cryptogram, the lines become shorter and shorter and the spaces between the letters become larger and larger. It almost seems as if the author of the cryptogram has run out of text. On the last line, there are striking repetitions of sequences of (3) signs, sometimes only distinguished by the addition or omission of dots. It is therefore very likely that the signs were only used to fill up the line and therefore cannot make any sense in terms of content (especially in the last 15 characters).

Summary

Original

APREDMEZUNEPAIREDEPIJONTIRESKET

2DOEURSQESEAJTETECHERALFUNEKORT

FILTTINSHIENTECUPRENEZUNECULLIERE

DEMIELLEEFOVTREFOUSENFAITESUNEONGAT

METTEZSURKEPATAIEDELAPERTOTITOUSN

VPULEZOLVSPRENEZ2LETCASSESURLECH

EMINILFAUTQOEUTTOITANOITIECOUUE

POVRENPECGERUNEFEMMEDHRENGTVOUSNAVE

QUAVOUSSERERLADOBAUCGEAETPOURVE

NGRAAIETPOREPINGLEOUEIUILETURLOR

EILJNOURLAIREPITERUNCHIENTUPQUN

LENENDELAMERDEBIENTECJEETSURRU

NVOVLENQUILNISEIUDFKUUNEFEMMRQ

IVEUTSEFAIREDUNHMETSEDETESUDRE

DANSDUUI●OOUQNDORMIRUNHOMMR

ESSCFVMM/PLFAUTNRENDREUDLQ

UUNDIFFURQECIEEFURTETLESL

Cleanup

PRENEZ UNE PAIRE DE PIJON

TIRES LES COEURS PESES O TETE CHEVAL

FUME L OREFILS T IN SHIEN TUCQ

PRENEZ UNE CULLIERE DE MIELLE E SOUFRE VOUS EN FAITES UNE ONGAT

METTEZ SUR LE PATAIE DE LA PERT O SI VOUS N VOULEZ PLUS PRENEZ LES CASSE SUR LE CHEMIN

IL FAUT Q OEUF SOIT A MOITIE COUVE

POUR EMPECHER UNE FEMME DHRENGE VOUS N AVE QU A VOUS SERER LAC O BAUCHES

ET POURVENIR SAJET POR EPINGLE OU D JUILE SUR L OREILJ

POUR FAIRE QITER UN CHIEN TURQENFUMEZ DE LA MERDE BIEN SECH FESSER QU N VOULEZ QU IL N I SE RECELE

A WOMAN WHO WANTS TO GET AWAY FROM YOU, SHE DETAINS YOU IN THE BEDROOM IN ORDER TO KILL A MAN

QU A SA FEMME PLESET PRENDRE QELQU UN DIVVER QE C IL E SURE ET LEAL

Modern transcription

Prenez une paire de pigeons. Tirez les coeurs, pressez[-les] à la tête du cheval.

Fumez l’orifice d’un chien turc.

Prenez une cuillère de miel et [de] soufre, vous en faites un onguent. Mettez [-le] sur la patée de la bête, ou si vous ne [la] voulez plus, prenez des casses sur le chemin.

Il faut que [l’] oeuf soit à moitié couvé.

Pour empêcher une femme dérangée, vous n’avez qu’à serrer [de la gomme] laque contre la bouche et obtenir un sachet de clous [de girofle] ou mettre de l’huile [de girofle] sur l’oreiller.

Pour faire à qu’un chien turc quitte [l’endroit] enfumez de la merde bien sèche. Fessez [-le], si [vous] ne voulez [pas] qu’il s’y cache.

Une femme qui veut se faire du mal met de [la] dature dans du vin pour endormir un homme.

Qu’il plaisait à sa femme [de] prendre quelqu’un d’autre que s’il était sûr et loyal.

Translation

Take a pair of pigeons. Pull out the hearts and press them against the horse’s head.

Give a mangy dog a smoke enema.

Take a spoonful of honey and sulphur and make an ointment. Put it on the animal’s food mash, or if you no longer want it, take laburnum from the path.

It is necessary for the egg to be half-hatched.

To prevent a woman from being disturbed [by bad breath], put shellac on your mouth and get a bag of cloves or drip oil on the pillow.

To drive away a mangy dog, burn dried shit. Give him a kick in the butt if you don’t want him to hide.

A woman who wants to do bad things to herself mixes datura into her wine to put a man to sleep.

That his wife is happy to take someone else, but only if he is reliable and faithful.

Schematic representation

Please include this source reference when using or publishing this transcription – even in extracts: © Daniel Krieg, www.labuse-facts.com

– Ruscelli, Girolamo (pseudonym: Alessio Piemontese): De’ Secreti del reverendo donno Alessio Piemontese. Prima parte. Venice: Giordano Ziletti, 1557.

– Hellwig, L. Christoph: Lexicon pharmaceuticum. Erfurt: J. Bielcke, 1714.

– Alexandre, Nicolas: Dictionnaire botanique et pharmaceutique. Paris: Hérissant, 1759.

– Brookes, Richard (M.D.): The Natural History of Birds. London: J. Newbery, 1763.

– Gardanne, Jean-Joseph: Recherches sur la mort des noyés et les moyens d’y remédier. In: Observations sur la physique, sur l’histoire naturelle et les arts, 1787.

– Woodall, John: The Surgeon’s Mate. 2nd edition. London: R. Young for N. Bourne, 1639.

– Charlevoix, Pierre François Xavier: Histoire et description générale de la Nouvelle-France. Paris: J.-B. Garnier, 1744.

– Journal des Sçavans, vol. 75, 1749.

– Le Vaillant, François: Voyage de M. Le Vaillant dans l’intérieur de l’Afrique, Tome 2. Paris: Leroy, 1790.

– Simoons, Frederick J.: Eat Not This Flesh: Food Avoidances from Prehistory to the Present. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994.

– Scheuchzer, Johann Jakob: Physique sacrée, ou Histoire naturelle de la Bible. Augsburg: C. U. Wagner, 1732.

– Walcher, Daniel (ed.): Food, Man, and Society: A Reader in the Anthropology of Food. New York: Macmillan, 2012.

– Bolakonga Bobwo: Les tabous de la grossesse chez les femmes Sakata (Zaïre). Kinshasa: Institut National de Recherche, 1989.

– Gadagbe, E. Z.: Conseils de santé à la famille africaine. Lomé: Éditions de l’Église Évangélique Presbytérienne, 1977.

– Pass, John: Clove Tree (Syzygium aromaticum). In: Useful Plants of the World, 1808.

– Franck von Franckenau, Georg: Flora Francica Aucta, oder vollständiges Kräuter-Lexicon. Frankfurt a. M.: J. A. Jung, 1766.

– Johannes von Cuba (Johannes Wonnecke von Kaub): Le iardin de santé. Strasbourg: Johann Grüninger, 1539.

– Chomel, Noël: Dictionnaire oeconomique. Paris: Nicolas Simart, 1740.

– Buffon, Georges-Louis Leclerc de: Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière. Paris: Imprimerie Royale, 1789.

– Weinmann, Johann Wilhelm: Phytanthoza-Iconographia. Regensburg: Hieronymus Lentz, 1739.

– Roussin, Jacques (ed.): L’agriculture, et maison rustique de M. Charles Estienne. Paris: Guillaume Auvray, 1594.

– Bonelli, Giorgio: Hortus Romanus. Rome: Typis Komarek, 1772.

– van der Aa, Peter: A Lady and Gentleman of Goa. In: La Galerie agréable du monde. Leiden, 1725.

– Linschoten, Jan Huyghen van: The Voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the East Indies. Transl. 1885. After the English edition of 1598.

– Acosta, Cristóbal: Trattato di Christoforo Acosta delle droghe et medicamenti dell’India orientale. Venice: G. Griffio, 1585.

– Ernsting, A. C.: Nucleus Totius Medicinae. Hamburg: Thomas von Wiering, 1770.

– Grandidier, Alfred: Histoire physique, naturelle et politique de Madagascar. Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1885.

– Pfeiffer, Ida: Voyage à Madagascar. Paris: Hachette, 1881.

– Rousselet, Jean: Femme Sakalava. In: Le Tour du Monde, 1902.

All articles Cryptogram

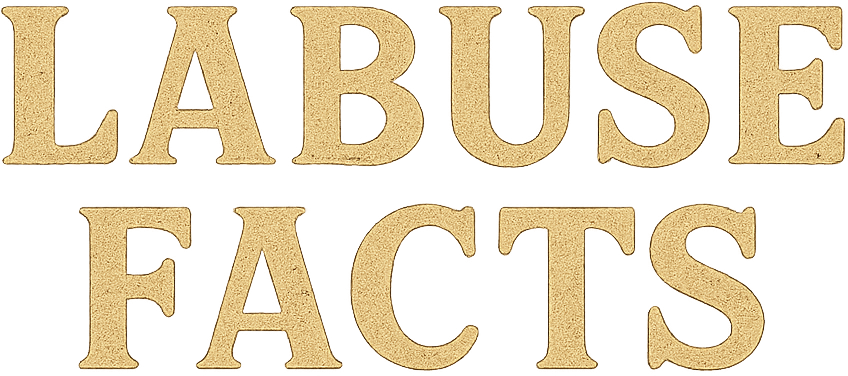

The cipher that has been sprouting the fantasies of many people in all its aspects for 90 years.

All articles La Buse

The life and work of the most famous French pirate of the 18th century.

All articles Backgrounds

Stories and history about the “Golden Era of Piracy”, La Buse and the cryptogram.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!