L’ORDRE DES FRANC-MAÇONS

With the publication of the book “L’Ordre des franc-maçons trahi” in 1745, a complete Masonic code was made available to the public for the first time. The author, later identified as Gabriel-Louis Calabre Pérau, describes in detail the structure and application of a graphic cipher based on a grid principle – exactly the same system that underlies the cryptogram from the “Flibustier mystérieux”. Pérau’s reference to the alphabet used is particularly revealing: It contains neither V nor J, as these letters were not considered independent in French at the time. The cryptogram, on the other hand, works with an alphabet that does contain V and J – which rules out the possibility that the document was written at the time of La Buse (died 1730). This contradiction sheds new light on the question of the origin and authenticity of the cryptogram – and has so far been largely overlooked by researchers.

In 1745, a book in French was published in Amsterdam in which the anonymous author reveals the secrets of the Masonic Order (there is also a reference to 1742; however, no copy of the book with this year of publication has been found). The complete title: “L’Ordre des franc-maçons trahi et le secret des Mopses révélé”. The author was later revealed to be Gabriel-Louis Calabre Péraut (1700-1767). He was prior at the Sorbonne and called himself an abbot, but was never ordained a priest. At first glance, one might assume that a traitor was at work here, but the author denies this:

“[My publisher] absolutely wanted to title this work ‘The Betrayed Masonic Order’. I was able to explain that this title carried an infamous note for the author’s person; I had to give in: but only on condition that I dispelled this abominable suspicion in my preface.”

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabriel-Louis_P%C3%A9rau

It seems that Abbé Pérau was never initiated as a Freemason. He apparently sneaked into the order out of sheer curiosity in order to be shown the rituals and symbols used and then to make them public.

The published code

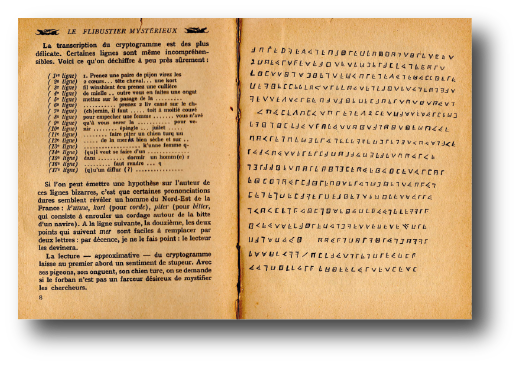

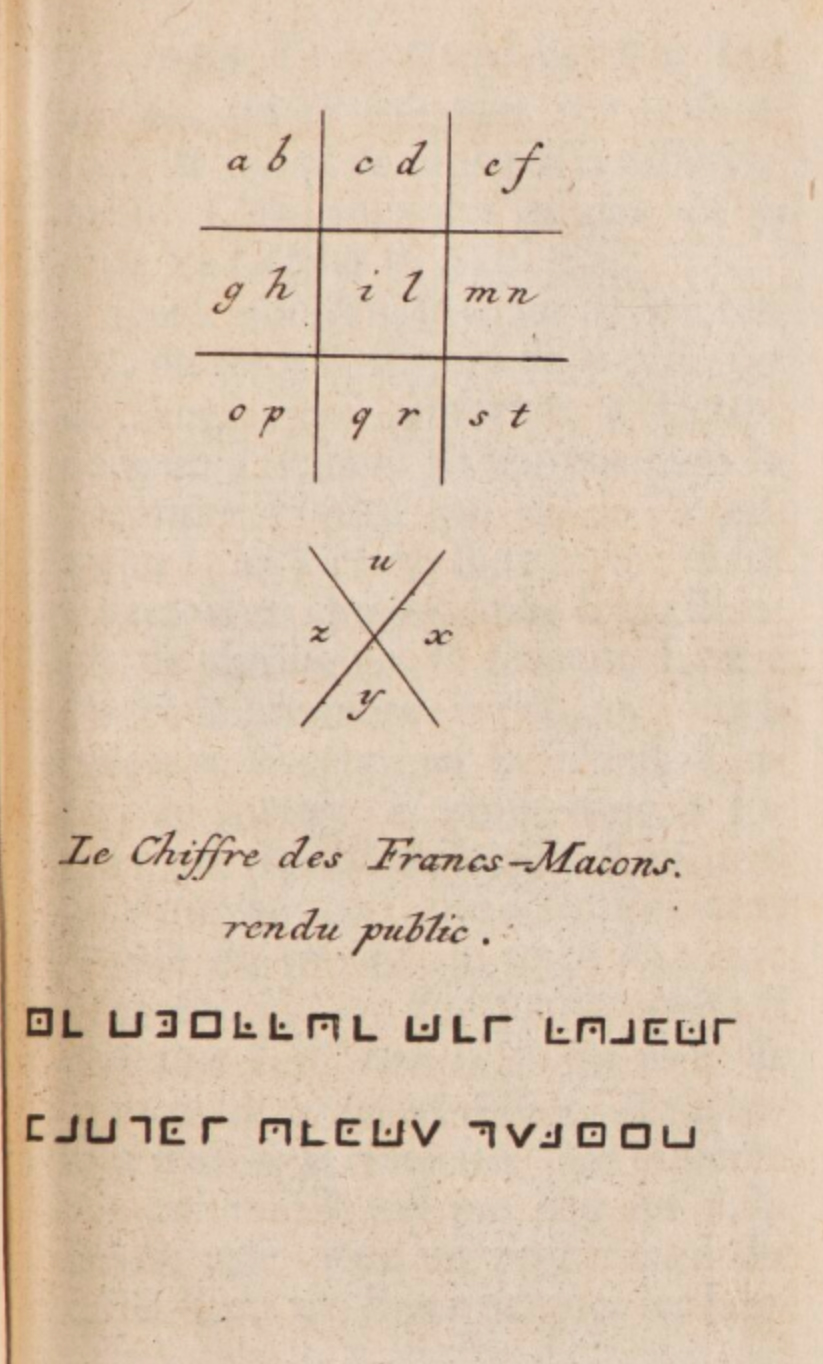

The “Chiffre des franc-maçons” is explained on page 142 ff. of the book.

“You can see from the engraved tablet that this figure consists of two different figures, one of which is made up of four lines that intersect at right angles and form nine squares or boxes. Only the center square is completely closed, the others are open either on one or both sides, and the side or sides of the opening are different in all of them.

The letters of the alphabet are written in this figure, two in each field, up to the t.

Then the second figure is drawn, which consists of just two intersecting lines: it forms four corners that join at the top and are all oriented differently. The letters u, x, y, z are written at these angles.

If you want to use this sign, you draw the figure of the box or angle that contains the letter you need. And since in the first figure, which ranges from a to t, the letters in each box occur in pairs and the point is to distinguish the second letter from the first, if you want to express the second letter, you put a dot in the figure that represents the box. So if I need an i, which is in the middle box, I draw a square box that is closed on all four sides; if it is an l, I draw the same box and put a dot in the middle; if I need a c, I draw a box that is open at the top; if I need a d, I draw the same box with a dot, and so on. This only applies to the letters of the first figure. For the second figure, since they are there individually, only the figure of the angle that contains them is traced.

After these explanations, one will readily understand the example in the illustration, where the words: ‘The Freemasons’ writings made public’ are written in the Masonic script.

The alphabet we see here is made for French, which does not use the k or the w. It is easy to extend to other languages by adding two letters and even the v consonant; just put three letters in one or two boxes and make two dots instead of one if you need the third letter.

If the gentlemen Freemasons change their cipher, which they will undoubtedly have to do in order not to expose their mysteries to desecration, I can teach them one that is demonstrably indecipherable. It also has the unique property that everyone can know the method and has the same tablets to use, and yet only the person to whom you write can decipher the letter.”

In this code, the variant with only 2 grids was used, just as in the cryptogram. The second-last section of the explanatory text is very interesting. Péraut explicitly points out that the code applies to the French language. He explains that K and W are missing because there were no words containing these two letters in French towards the middle of the 18th century. The consonantal V, on the other hand, he suggests for other languages, while he does not mention the missing J at all. The explanation for this is that both letters – J and V – were not considered part of the French alphabet at the time of publication. V was equated with U, J with I. This corresponds to the Latin spelling tradition. Let us realize this once again: The book was published in 1745 (1742). The alphabet used in the published code contains neither the V nor the J. For the cryptogram, on the other hand, a code was used in which only the W is missing (X and Y have a place in the grid, but do not appear in the document). In both cases, the grids were filled in according to the same principle: Always in pairs along the alphabet, in one case according to the time without W, V and U, in the other – probably also according to the time – only without W (which was only included in the official French alphabet in the 20th century). The fact that these two letters J and V are present in the alphabet of the cryptogram code rules out the possibility that Olivier Le Vasseur wrote the document between 1721 and 1730.

Strangely enough, neither Charles de La Roncière nor other researchers have yet noticed this fact.

And one thing is clear: from the publication of the book in 1745 at the latest, it was possible for anyone who had access to it to write a text in the Masonic script.

Sources mentioned:

– Pérau, Gabriel-Louis Calabre: L’Ordre des francs-maçons trahi et le secret des Mopses révélé. Amsterdam: Jean Neaulme, 1745.

All articles Cryptogram

The cipher that has been sprouting the fantasies of many people in all its aspects for 90 years.

All articles La Buse

The life and work of the most famous French pirate of the 18th century.

All articles Backgrounds

Stories and history about the “Golden Era of Piracy”, La Buse and the cryptogram.